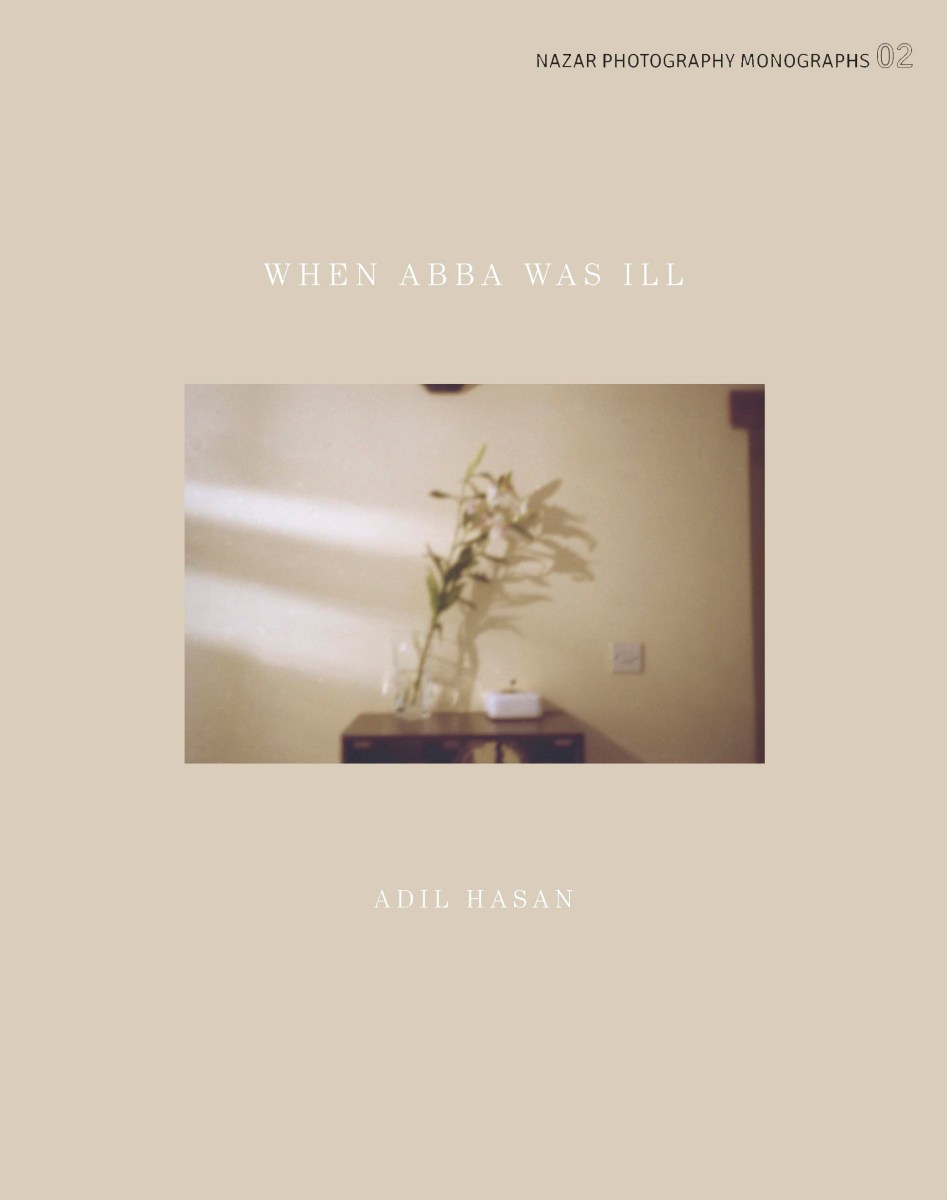

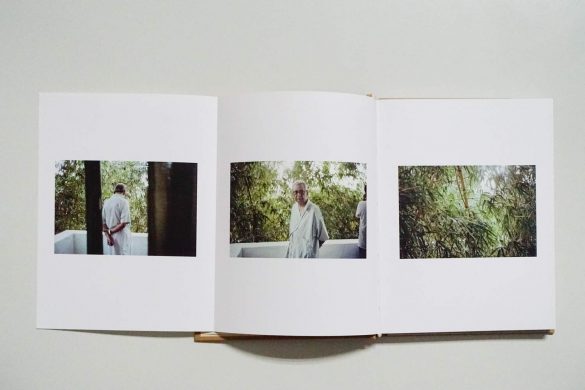

‘When Abba Was Ill’ is a photobook by Adil Hasan, a Delhi based photographer. The book is a gentle portrayal of the six months that followed after his father, Mahmood Hasan was diagnosed with Seminal Vesical Carcinoma, a rare form of cancer. It was published by Nazar Foundation and launched at The Jaipur Literature Festival, Jan’14. The photographs are shot on old film cameras, hence, are soft and bring a sense of warmth, like that of a family snapshot. ‘When Abba Was Ill’ is wistful, poetic, and has an elegiac feel to it, so much so, that it prompts lachrymose for the faint-hearted. Adil Hasan while having worked for commercial projects like Vogue, GQ, and Motherland has, on the other hand, kept himself occupied with other personal projects mentioned later in the interview. I met Adil at his beautiful apartment in Delhi and he was kind enough to offer me a cup of coffee. Our interview started on such a note that Adil while answering my questions, would politely stop to enquire about my sugar, milk and coffee preferences and get back to answering very diligently.

How and why did you switch from an Economics Graduate to a full-time photographer?

So I did my schooling from Jamshedpur and studied Economics from Mumbai. At home, we had a semi-classical upbringing. My father was fond of reading, my brothers were older and introduced me to good music straight away. We watched good cinema, I kept myself (geekily)updated with the books and luckily figured out my way with cameras easily. Anyway, I was going through a tumultuous ‘Undergrad Phase’ and decided to assist fairly commercial photographers. I think BA courses in our country are so simple and spare you a lot of extra time. I jumped from one commercial photographer to another for 3 years and soon realized that I was caught in a bubble and there was no way out. I knew that this couldn’t be ‘it’, you know. I needed a change of perspective and with much consideration went ahead with a photography course in Unitec, New Zealand. I do feel that the scenario of photography colleges/courses in India is still ill-updated and very rarely are the teachers, active practitioners, of photography. It was Unitec where I was introduced to several brilliant Indian photographers.

Have you worked on any other personal projects (series) like ‘When Abba Was Ill’?

Honestly, ‘When Abba Was Ill’ was not planned (obviously) and I wasn’t acting on things or making decisions consciously. But with other projects like ‘Auckland- The Urban Project’, ‘The TV’, and ‘AMU- Aligarh Muslim University’, I knew what I was doing and making, although, every project took its course with time, which isn’t always planned. I do feel I could have worked a little harder on the names (laughs). Personally, I feel that working on personal projects is in itself a very different experience and for the longest time, serious photographers have been doing it. It came to us (South Asia) much later but I feel we’ll get there eventually. Pictorialism on the other hand, at times, feels redundant to serious photographic circuits but some people, for example, Jeff Wall are extraordinary and make every image as a single image but it’s so consistently a single image that it turns on its head and becomes a series.

How did ‘When Abba Was Ill’ turn into a photo-book and what was it like to work on something so deeply personal and sensitive?

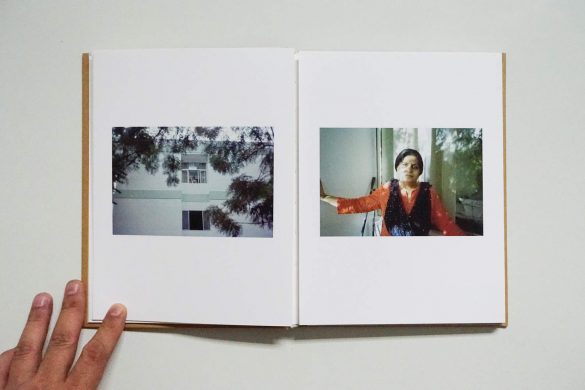

As I’ve said earlier, to photograph the six months i.e. my father’s diagnosis to his death, was not a conscious decision. I am a photographer, so making pictures comes naturally to me. I remember rushing to Bangalore after the news of his diagnosis and in haste forgetting to carry my cameras. So all I could use at that point of time, was this ‘old family camera’, Yashica-G, that had been lying in my brother’s drawer for ages. Halfway down the treatment, the doctors suggested we take Abba to Jamshedpur, near to family and friends. I had ran out of films, so bought a few Kodak films of which some had already expired, hence the softness to the images. Later on, I had them developed at a Quick Service Store that develop films not manually but by machines. It’s a clumsy process and I dreaded to even look at the results but to my surprise, the photos had turned out to be very warm and gentle. After my father’s demise, it took me a while to go back to the photographs. The first person that I showed the photographs to, was, Sanjeev Sethi. He is a photographer as well as a publisher. He sought in the photographs a book and readily offered to help me through it. Meanwhile, Nazar Foundation was to release its 2nd monograph series and Prashant Panjiar thought the book was a perfect fit. It was sensitive, contemporary, and had no intrinsic commercial value. Then I asked for approval from my brother, sister-in-law, and my mother. So Sanjeev became the editor, Nazar Foundation the publisher and Pragathi in Hyderabad printed our book.

I would love to know more about the editing process of ‘When Abba Was Ill’. Could you describe it briefly?

Sure! It took us around a year to edit the book. Sanjeev’s drawing-room was littered with photos the whole time and we worked really hard to do justice to the book in certain ways. So when you look at the book, the editing makes it feel like my gaze is very telescopic and specific but it wasn’t like that. I was, in fact, shooting very wide and was lost in my own world of boredom and getting in terms with my father’s illness. For starters, we thought of starting the book with one of the poems by Epicurus written in my father’s diary and ending it with one of Rumi’s.

We had to work out a narrative where I could include a major part of my father’s life. His life in Jamshedpur and the 21 years he dedicated to Tata Steel.

Even the first photograph is that of my sister-in-law pointing out at something almost like a premonition as you proceed ahead with the book.

Although there was a time, during the editing process, when I had decided to not go ahead with the book. That’s the thing with deeply intimate projects, that it almost feels wrong to put it out there in the world. You question and you overwhelm at the sensitivity of the project. That’s when we came up with the idea of gatefolds within the book. These gatefolds divided the book into two parts- When Abba Was Ill; When Abba Was Ill, who was I?

So if you look at the book without opening the gatefolds, You won’t see my father.

The gatefolds serve as a symbolic gesture, they protect my father and the sensitivity of this symbol is why we restarted the editing again. Now there were also some ‘happy accidents’ that took place within the cameras. For example, the Yashica-G I was using during those 6 months, had a broken winding mechanism. So each time I would take a click, I had to wind it afterwards to take another photograph. Because the winding mechanism was broken, in between the space for 2 negatives, a 3rd one got superimposed and what can I say, I didn’t see it coming!

For the past 5 years, each time I visit Jamshedpur to see my mother I try to click the memories of my hometown and my mother’s life (now). Basically, the aftermath of ‘When Abba Was Ill’.

Mahmood Hasan passed away in November 2012 in Jamshedpur, his hometown where he had worked with Tata Steels for 21 years. History, Philosophy, and literature were among his varied interest. Books, music, and an intelligent conversation brought him pleasure, and the company of his diverse friends, comfort.

All images by Adil Hasan.

Text and Curation by Afreen Akhtar.