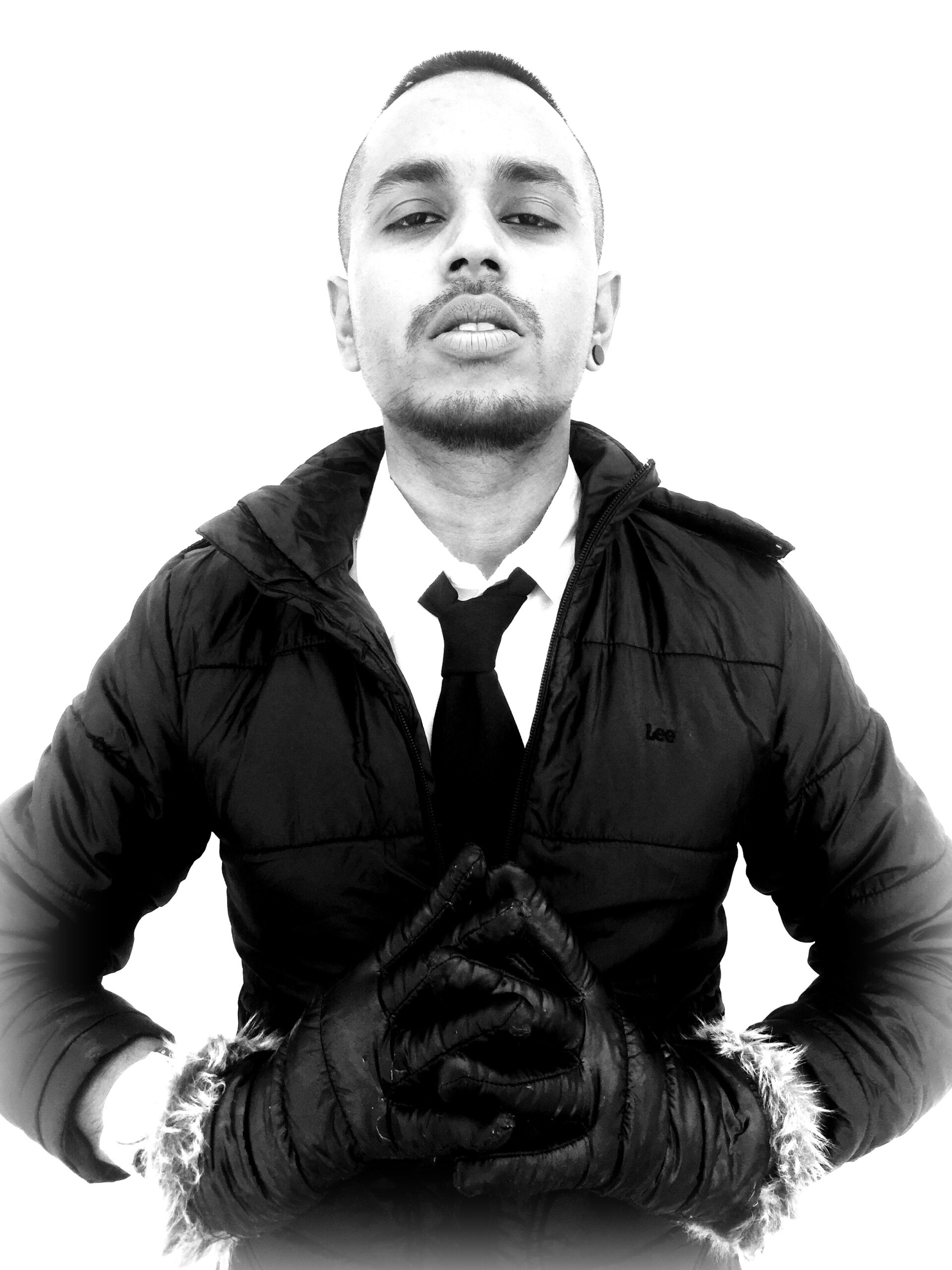

Vik Feyago, the one-man rap act behind Feyago, is a Kolkata based, music-mingling machine. With cultural influences that stretch from WuTang clan to Bob Dylan to more recently, Baul folk music, Vik combines instruments as diverse as the duitara and the theremin to produce the oozingly catchy genre of folk rap, a term he has coined. In 2014, he won the VH1 Sound Nation award for the Best Hip Hop Act of the year for his single Someday, and an unstoppable journey to explore the musical landscape of the East began since, with his much-known series, Hip Hop Homeland (in collaboration with 101 India) breaking ground in its involvement with rappers from the North East, who spoke of the disavowed manner in which their music and politics is treated by mainstream contemporaries. Vik releases his first complete EP, Woke, in April, a labour of love after many years of touring and singles. We caught up with him recently, and a chat ensued on his new album, the music scene of the North East and the larger politics of what the recent popularization of rap in India spells and problematizes.

Hey Vik! We really liked your new EP and its melange of various musical trends from Meghalaya and Bengal with the genre of rap. What was most noticeable was that this is very different from your earlier tracks, such as Money and Someday. We also know you have recently begun to explore Indian folk music traditions more, such as your Baul Rap track released with 101 India. Could you tell us more about this shift from your earlier music to your current exploration, and what brought it about?

My music sounded rather underground and amateur for the first two years. You have to realize that this is a twenty-something-year-old, out there on his own, trying to introduce a new genre without any guidance, financial support or strategy. You could hear the stress in my vocals because my life was about making ends meet, traveling in the most economical way possible, maneuvering my way around manipulative event managers, crashing at friends’ places and using their wardrobes for gigs. I literally screamed into the microphone in the studio and on stage. Each video was self-directed on a zero budget. However, as time went by, the rap genre caught on and the work began paying off. This resulted in a calmer mind and a more disciplined, mature approach towards the music. One awkward winter evening at Hard Rock Cafe, Worli, “Someday” won the VH1 award for Best Hip Hop Act. This changed my life in many ways.

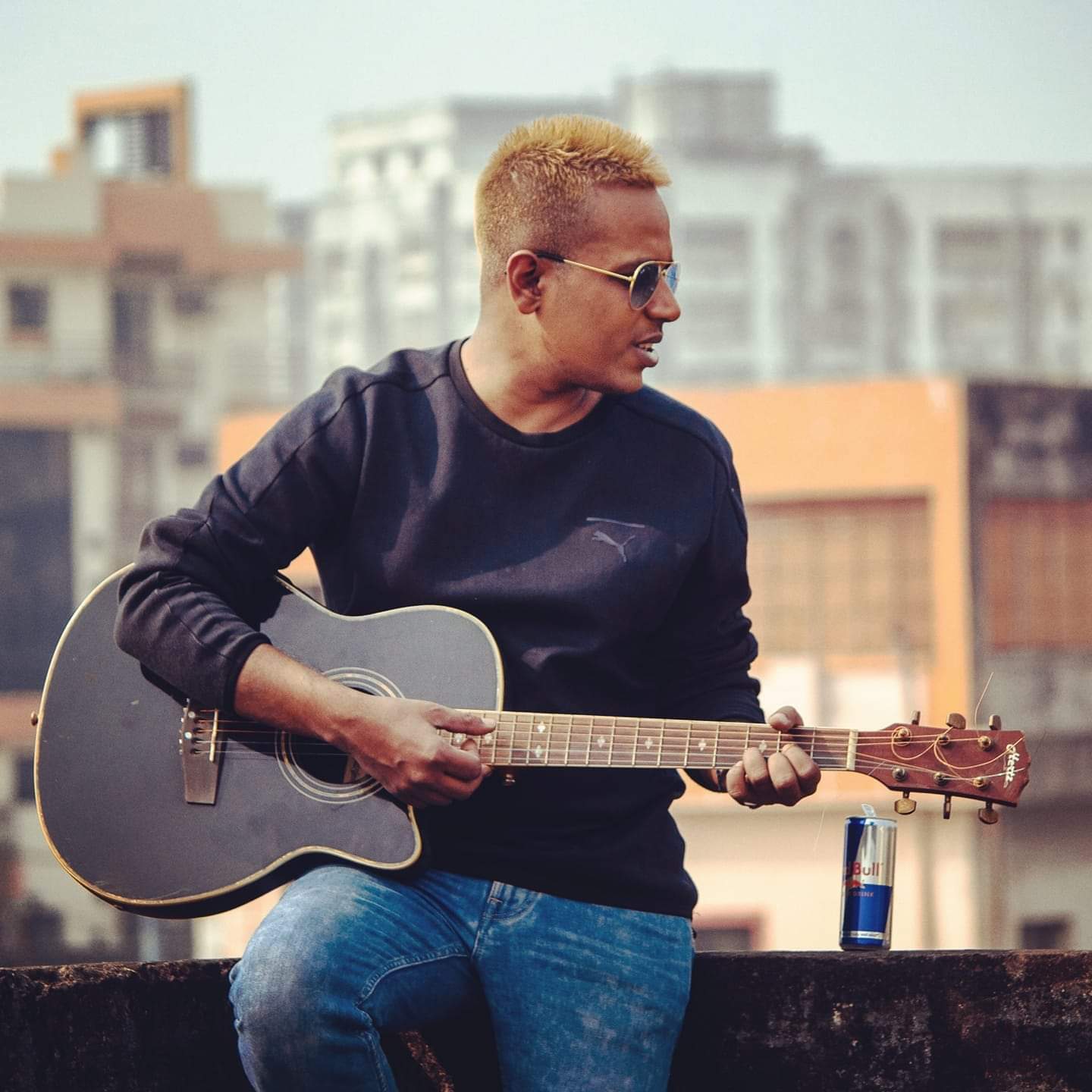

I began touring extensively by 2014, managing my own tours along with VH1 and MTV Indies. The music began sounding happier, and more structured. My voice sounded calmer and deeper. Travel opened my eyes to a whole range of folk music, some of which I have tried to incorporate in this EP. You will hear Baul, Khasi, Naga, Nepali, Meitei, Assamese and Bhutanese folk in my upcoming projects. This will be called Folk Rap, a sub-genre I am trying to create that blends earthy, folk instrumentation and soulful, raw lyric with modern rap and trap sounds in order to generate an Indo-western vibe that today’s India can relate to. Hopefully, in ten years time, Folk Rap will be a popular sub-genre!

Do tell us more about how you began with rap. Your influences, who you used to listen to, and your journey.

As a kid, I grew up doing theatre, public speaking, elocution, debate, and poetry. I listened to all kinds of music. My influences would range from indie, jazz and folk artists like Bob Dylan, Thom Yorke, Passenger, Tracy Chapman, Bon Iver, Louis Armstrong, AR Rahman and Frank Sinatra to urban music legends like Tupac, Biggie, Kanye, MJ, Nas, WuTang, Eminem, Chance, Jay Z, Lil Wayne and Frank Ocean and Kid Cudi. My biggest inspiration, however, is my family, the difficulties I have faced and the love and support I have received from my fans, in that order.

My journey started out in 2009 when I was a marketing student in Birmingham, UK, when I was first introduced to music production by a close friend from university. When I began composing melodies and turning old poems into rap lyrics, my first instinct was to drop out of university and pursue music as a life choice. And so I did. I came back to India due to personal reasons, reasons which manifested in a long spell of pain and struggle, both financially and emotionally. This was probably why I began writing lyrics to my own music. Turns out, composing can be extremely therapeutic! It helps you to channel your emotions towards something positive and reinforcing. I began making a lot of music at home.

I also worked as a freelance graphic designer in order to make ends meet. My job introduced me to an event manager who decided to visit my residence for some graphics work on the 20th of December, 2012. On that day, he noticed that my laptop had over three hundred unfinished songs. He was immediately willing to give me a chance to perform for his crowd. On December 31st, I had my first live show in Stadel, Kolkata. After that, I decided there was no looking back! I traveled to Nepal, Sikkim, Manipur, Bhutan, Nagaland, and Arunachal Pradesh, doing gigs for a minimum wage that just about covered my travel expenses. I managed myself and often used a different voice in order to score gigs. I became the first touring rapper with a steady flow of shows.

Gradually, I began exploring the rest of India. Today, I have performed at over two hundred venues including some of the most popular festivals, colleges and gig venues in the subcontinent, having represented many leading brands, introduced several artists to the game and managed to create an identity called Feyago, an inspiration to young artists across the country who needed proof that one can succeed without having to compromise on identity, values, and quality of craft.

Despite being an active artist for many years, including winning the VH1 award, and having a number of tracks out, you only released an EP now. What motivated this?

We live in a world where artists can no longer sell physical copies of their albums. Making and distributing music has become very easy and this has led to a huge surplus of supply over demand. Releasing music has become very easy but having a lasting impact on the listener is increasingly difficult now. A song is no longer a song, it is an audio-visual experience that needs to pack the right punch. Musicians are forgotten as easily as they rise. Creating a brand is easy but making the brand last, in the long run, is very more difficult decision-making process.

I have created more than three hundred songs on my laptop and was very tempted to release many albums over the last six years. However, I always decided against an EP or an album because it just didn’t feel like the right time. I figured that in order to tell a powerful story, one must have many experiences and the maturity to put them down on paper. Having traveled as a rap artist for six whole years gave me a huge chunk of life experience. I have also managed to tone down the anxiety and gather composure instead, something which is very essential to create any piece of art. Patience is another virtue which can work wonders. It’s all about taking as much time as required in order to find your own unique sound. It is very easy to follow the trend and hop on to the gravy train, but one must ask themselves questions about sustenance and long term goals in order to secure a permanent place as a musician.

I think I am finally in a state of mind to create something official! I will be releasing three EPs this year, the first of which is called “Woke”. The EP features five songs that will explore various aspects of modern society. “BrownTown” talks about India’s obsession with fair skin. “Why” points fingers to the major decision-makers in today’s world. “Legalise” talks about the benefits of legalizing marijuana in India. “Mard” addresses the rape culture in India. “1998” explores nostalgia and compares today to the happier, simpler past we grew up in.

As a rap artist, how do you regard your contemporaries and the genre of rap in India which has now with rappers like Divine moved into the more hyperlocal and contextual, with an embracing of local dialects. At the same time, as demonstrated in your work in the northeast, the dynamics of the region do play into it, with not many people hearing the work of the musicians there. So while a new trend in rap emerging, it is still subject to other dynamics and pitfalls of the region, and the idea of the nation projected and represented only by the few. How do we address this, in the capacity of the more mainstream, balancing regional recognition without tokenism and fetishizing?

Being an integral member of Indian rap community, it fills me with great joy that artists like Divine and Naezy have managed to popularise local dialects within rap music, even though it is still Mumbai-centric. When hip hop arrived in India, it was adopted by Bollywood as an extension of club/ pop/ edm music. Rap became synonymous with party songs. Every other song which had an “item” dancer also began having an “item” rapper. With the introduction of hip hop from the streets and slums, the country was introduced to the real meaning of rap – rhythm and poetry. Art is born out of struggle and pain. I am glad that this can now be monetised at a mainstream level.

Having said that, we must also remember that we are at the birth stage of hip hop in Asia. Only one community in one city has managed to attain mainstream recognition. Poverty in India has been fetishised for many years now (Slumdog Millionaire, City of Joy, Shantaram and countless other examples) and is a very effective way to promote just about anything new. It will take longer for communities from the East to reach out to mainstream audiences because of the acute lack of funds, marketing expertise and networking required to make it big in today’s world. Also, there’s a question of saleability. We live in an era of reality series where the backstory is so much more important than the craft itself.

Do elaborate more on the track Why, and the Duitara community’s music. As you are possibly one of the only rap artists in the country interacting with folk traditions from the East, what is your interaction usually with the communities you engage with? How open are they to incorporating Rap with their traditions, and how do you go about introducing yourself?

“Why” is a powerful set of questions asked the post-adolescent youth who is no longer naive enough to believe that society is at its prime. In order to match the depth of the lyrics, I have used melodic duitara and choir chants from Shillong along with the Japanese taiko drums and a monotonous, passive-aggressive vocal pattern. This song works particularly well at colleges where the youth can relate to the state of mind I was in when I wrote “Why”. The song uses very straightforward rhyme schemes and rhythm unlike “BrownTown”, which uses a Baul folk rhythm that is more jovial, upbeat and groovy.

The culture in the East is incredibly diverse. Some of my folk influences come from the Bauls in Bengal, Tamang and Lepcha music from Nepal, Sikkim and Darjeeling, Angami and Ao warrior chants from Nagaland, Khasi instruments like the duitara (also found in Bengal), Meitei folk melody and Dzongkha music from Bhutan. Folk blends really well with rap because both forms of music adopt an honest, realistic, holistic approach to the creative process. Eastern communities have a rich history of folk music and one can spend a whole lifetime dedicated to exploring sounds from this region. Contrary to popular belief, they are very friendly and welcoming to outsiders!

I was fortunate enough to have met some wonderful people who introduced me to a whole world of indigenous, tribal and regional folk sounds from the East. I always try picking up the languages and customs in order to blend with several communities. The East is a melting pot of diverse culture when it comes to the food, language, tradition and value systems. It is exhilarating to get the opportunity to explore remote areas and to try to work on projects with people who have never seen the insides of a studio but are gifted with eclectic musical sounds passed down through the generations. This is probably one of the best parts of my job!

However, as is the case with many other sectors (minerals, farm goods, SME factories, start-up firms and hospitality industries for example), the East is just about beginning to boom. Hopefully, there will be a day when the entire nation is rapping along to some Nepali or Khasi rap song. Hopefully the country will begin to notice just how advanced the East is when it comes to music, fashion, art, and other creative fields. One hopes that the increase in popularity of the Mumbai local sound can act as a gateway to people opening up to a whole range of local sounds from other regions within the country.

Any parting words for your fans, and about the album? If you had to sum it all up in a sentence, what would you say?

The “Woke” EP is designed to evoke a sense of purpose and promotes the idea of thinking for yourself instead of blindly following leaders, elders and decision makers. If I had to sum up the project in a single sentence, I would say “open your eyes, decide for yourself, be informed and stay WOKE”.

Text by Anandita Thakur.