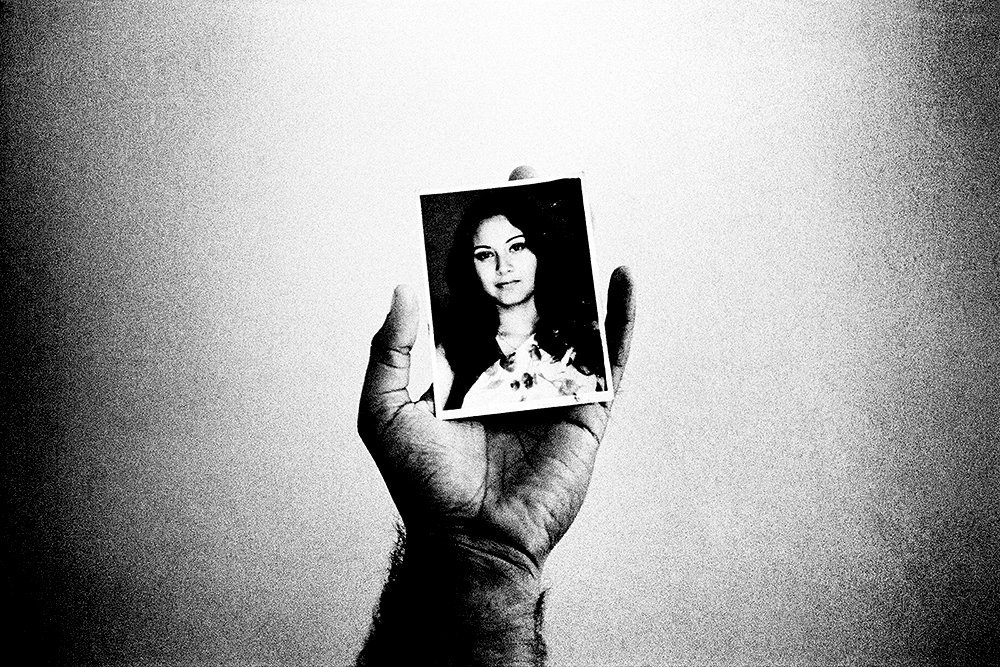

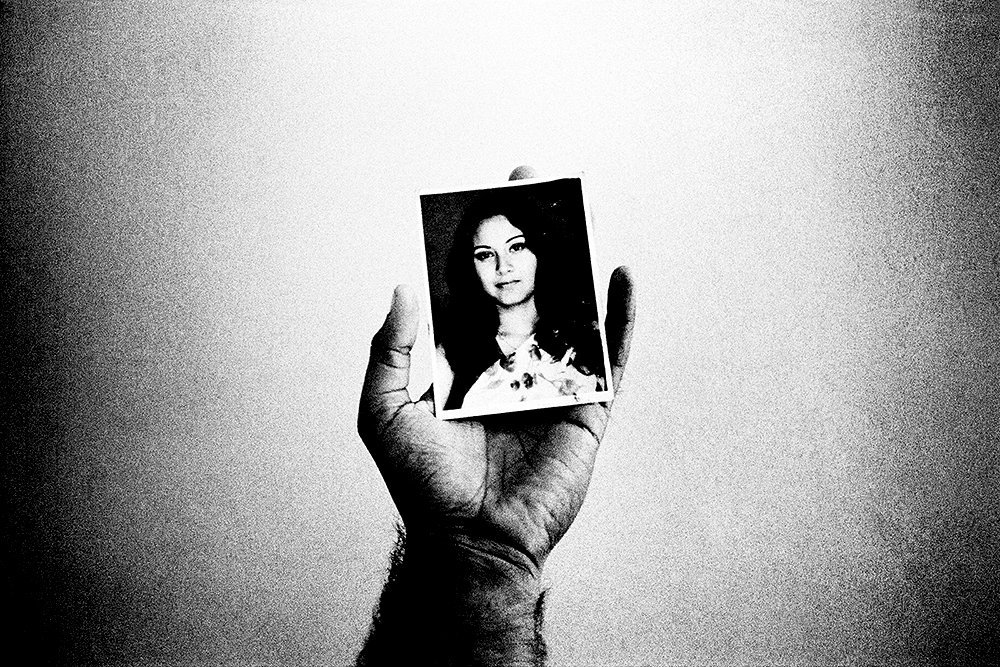

There is something absolutely magnetic about Sohrab Hura’s work. The dark, textured images that tell vivid stories of the life he’s lived and the people he’s met create a vortex that sucks you into the narrative that’s hard to look away from. Sohrab’s relationship with photography was sparked by personal experience. When he was 17, his mother was diagnosed with schizophrenia. This was when he began making images of his mother, his family, and his friends as a way to experience all the things that were about to disappear. He picked up the camera not as a choice, but out of a need to be able to survive as he coped with his mother’s illness. Sweet Life, a compilation of this body of work, later took the form of film, complete with a score created by Sohrab.

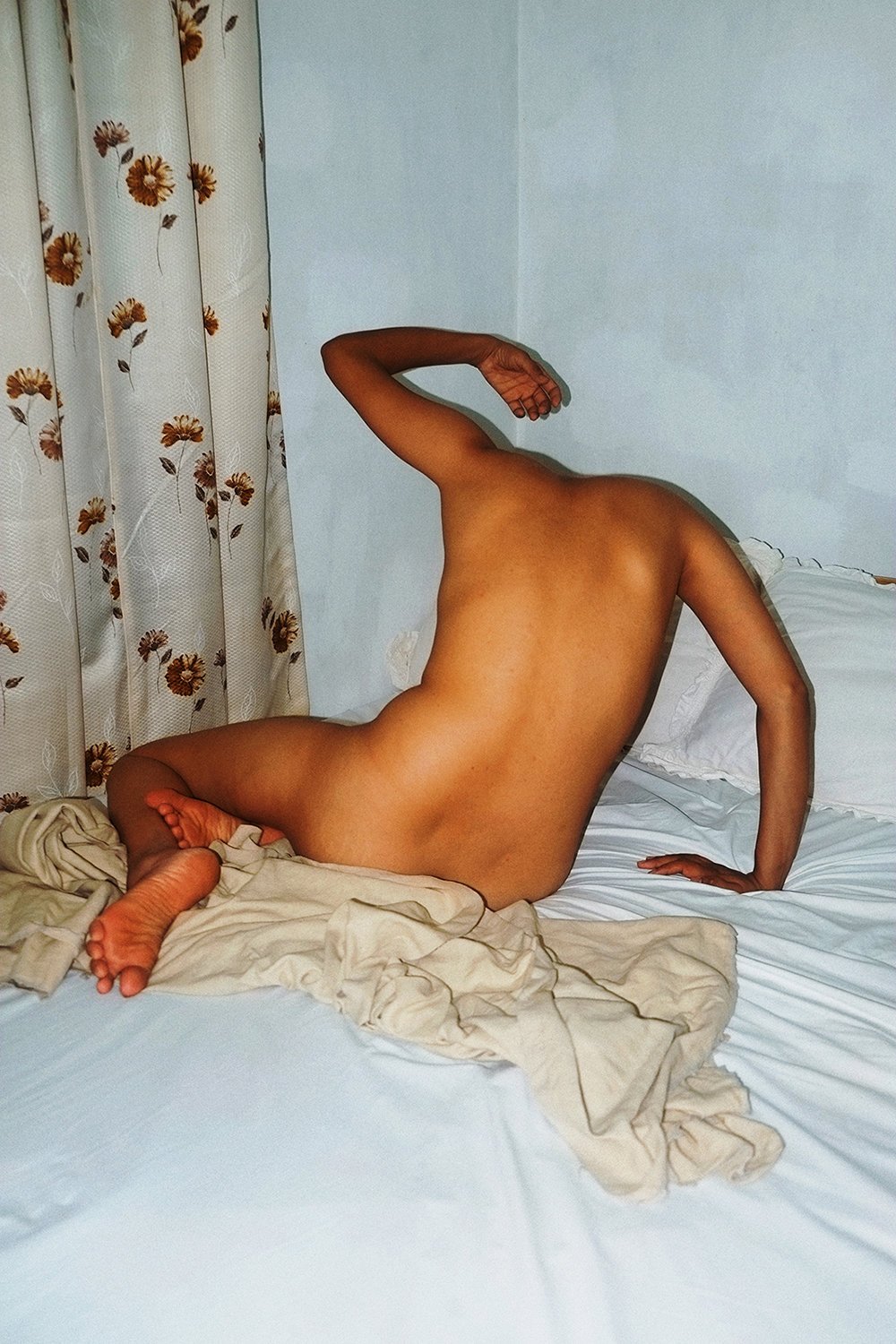

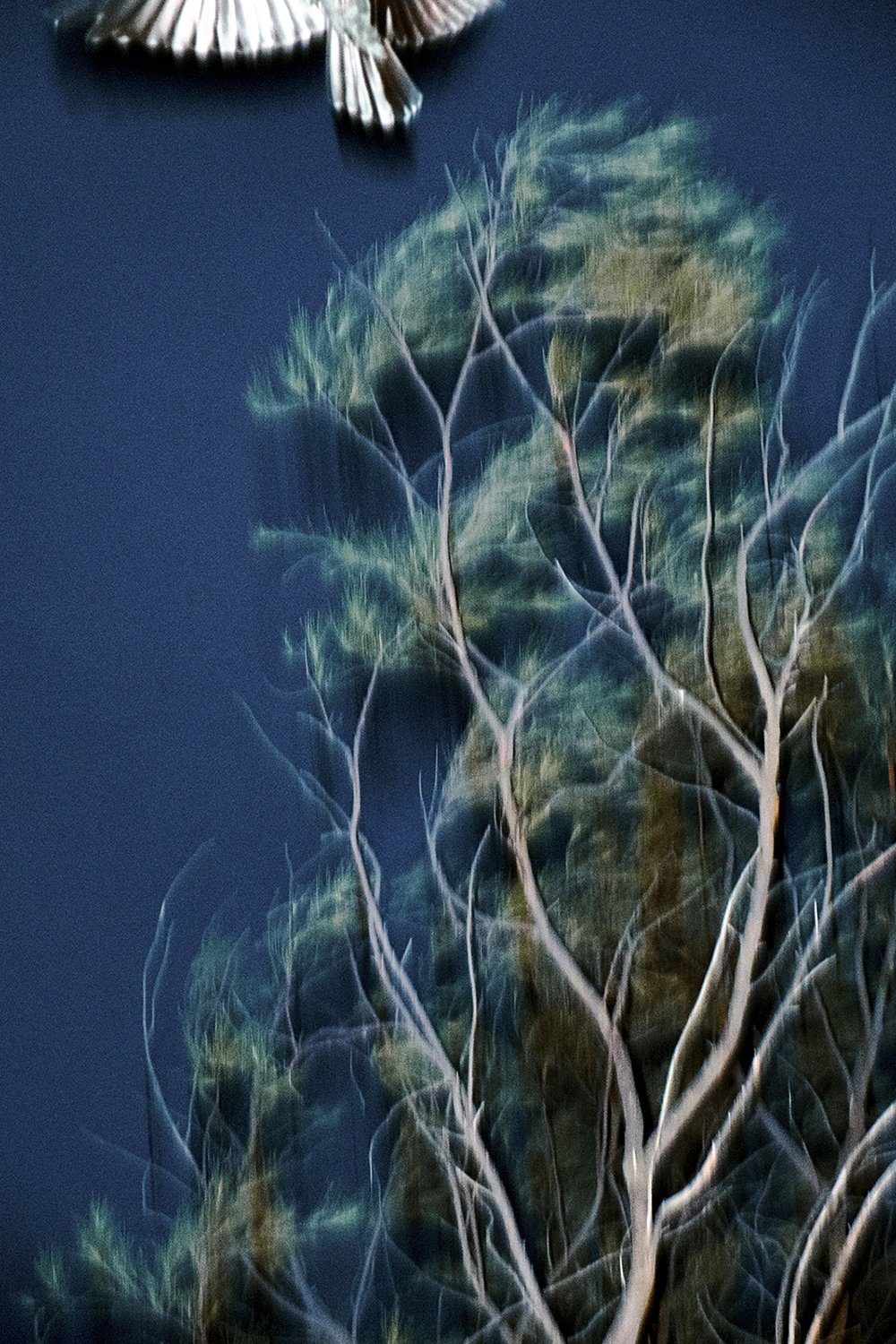

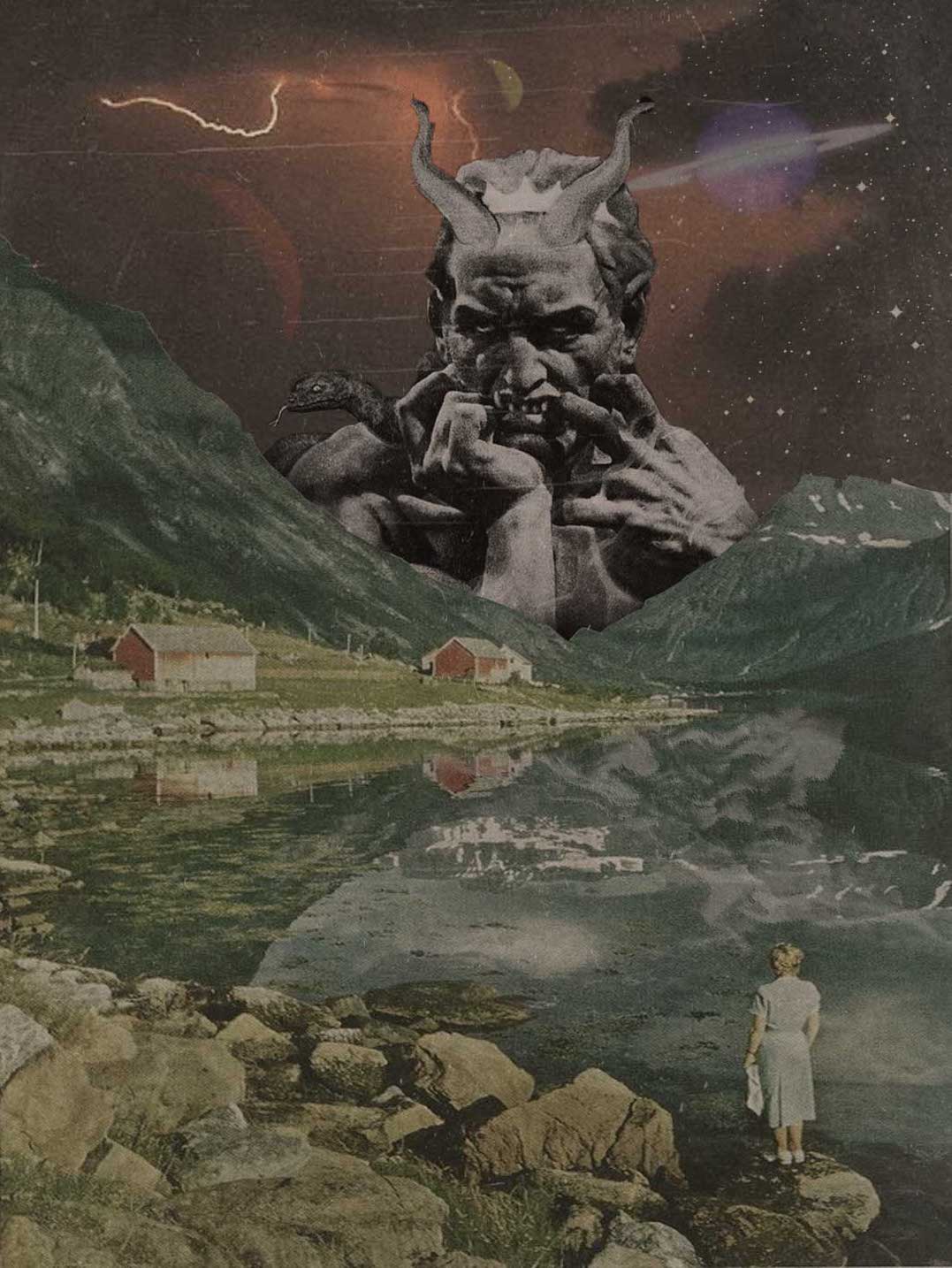

His experiments with moving image and sound continue in his latest work The Lost Head and The Bird. The photo essay-turned-film explores the present socio-political climate in India and wades through the undercurrents of caste, gender, religious and political violence. The project was celebrated at the Oberhausen International Short Film Festival, Arkipel in Jakarta and will travel to the International Film Festivals at Moscow and Vancouver later this year.

The Magnum Associate Member talks about listening to photographs to create soundscapes and the fear that soaks into his mind when creating new work.

Tell us about your short story, The Lost Head and The Bird, from your ongoing photo essay The Coast. Who inspired the character of the protagonist Madhu?

The characters are drawn out of encounters that I’ve had with people in the course of making the work. Although in the story, Madhu could be any ordinary person around us. There is also a fortune-teller in the story and there is a clear power structure between the two. Madhu does whatever the fortune-teller tells her to do out of helplessness, and out of her own superstitious beliefs. But the fortune-teller repeatedly cons her by selling her a crow and telling her that it’s a parrot with a bad temporary cough.

At its end, the story loops back to the beginning because this turns into a never-ending cycle. I have also inserted myself into the story as the idiot photographer who has heard of the woman with no head and wants to photograph her. With the way things are today, with violence of all kinds and with access to technology and distribution platforms, bystanders do nothing but remain voyeuristic. I sense the same tendency in myself as a photographer and hence I became that idiot photographer. But the truth is that everyone watching the film is an idiot photographer.

What does the metaphor of ‘the lost head’ allude to?

The character Madhu has lost her head because a lover had stolen it when he could not have her. So she is trying to make her way through life without her head, and hence without much agency, only to be taken advantage of by someone with power. The lost heads I’m hinting at are of course very different, but I will leave it up to the people who see the work to find them.

The Coast documents ‘the wonderful and vicious things that happen along the Indian coastline’. Let us in on your experiences while shooting the series?

I was trying to construct a psychological landscape. The Coast is about the edge, the margins, a sort of a tipping point. The actual coastline is just a window into this psychological space. Please excuse my stupid example here: Think of it as a balloon that I keep blowing air into. What one sees is the surface of the balloon that keeps inflating. At some point, that balloon will burst, but what I want to do is to take you where you start to sense that the balloon might burst any moment. That is my place of interest. The literal coastline of this country that I’m using in my work is only that surface of the balloon. But the work is actually about all that air being pumped into that balloon and that point from where one might sense that the balloon might burst.

What is the larger vision for the project?

I never have large visions for any of my works. I prefer to slowly build layer upon layer as and when new possibilities and directions arise. Right now, it’s in the form of a film.

Sweet Life is a composite of two bodies of work, Life Is Elsewhere and Look It’s Getting Sunny Outside!!!, both of which explore your relationship with your mother and home. What was different about your approach to the second chapter of the story, as compared to the first?

After I finished Life Is Elsewhere, I had started working with children as part of a photography workshop. The way they moved and approached photography in such a carefree way made me see the stiffness in my own way of working. There is a physicality to making photographs. Your movement (or the lack of it) can affect the sensibility with which you make those images. In Look It’s Getting Sunny Outside!!!, I tried to shed the baggage of being a photographer and look for a way of being more straightforward.

The project took ten years to complete. What did you learn about yourself and your understanding of photography along the way?

I’ve changed as a person, as well as a photographer and both positions, affect each other. As a photographer, I’ve gained more distance from the medium. That is not to say that I don’t care about photography, but I’m now more at ease coming into it from different positions. And because of that, photography seems far more malleable than it ever did. The thought of applying the same kind of photography, in terms of its language, across all my works started to feel absurd because it would mean remaining stagnant. As a person, I am sure I have changed but I’m happy to not think about it right now.

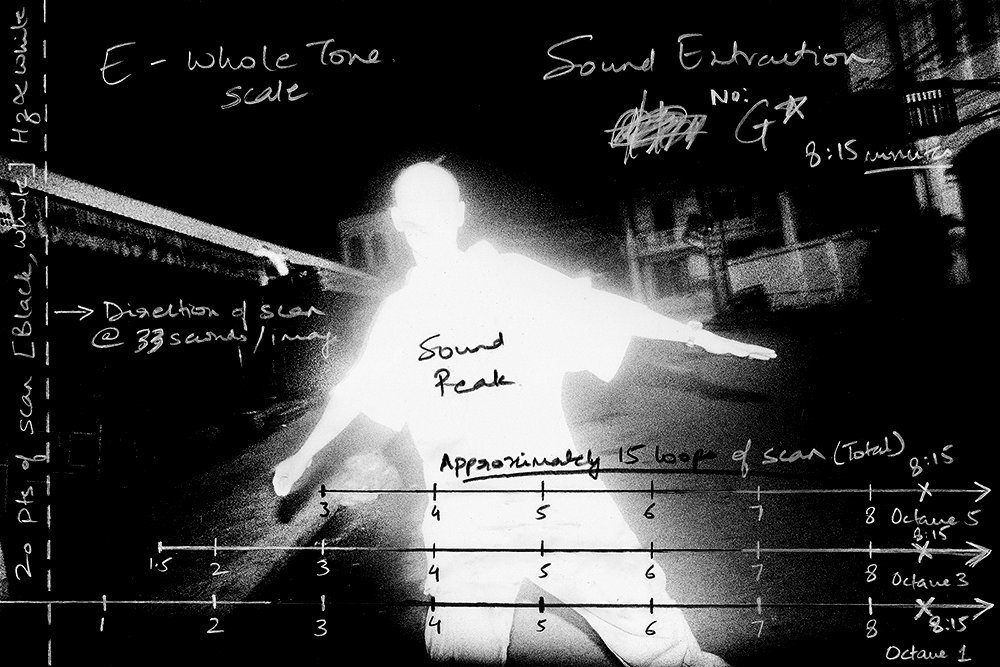

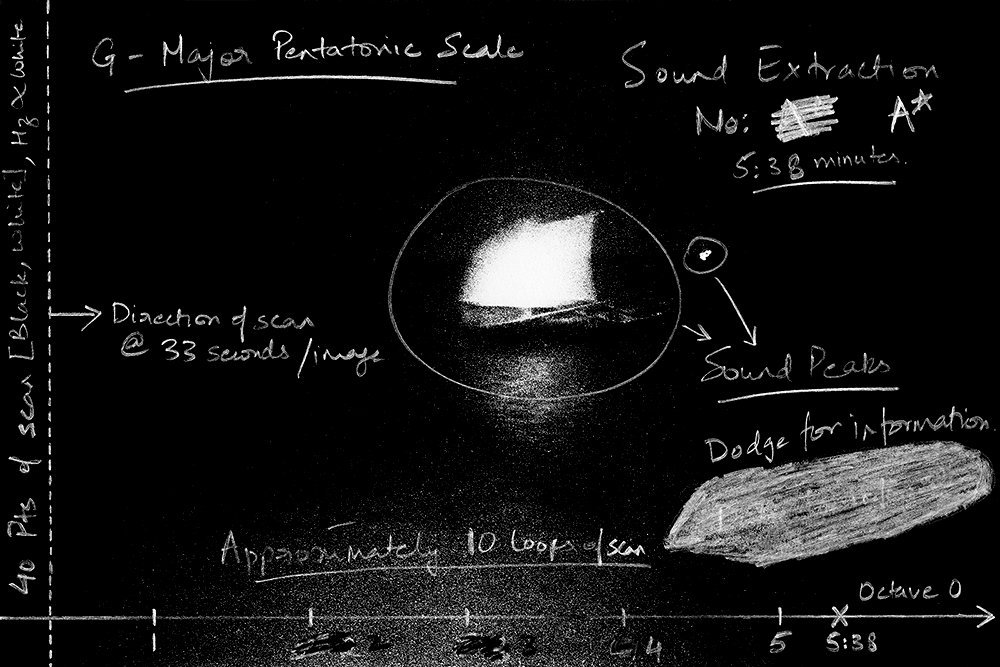

You created the score for Sweet Life by turning the light exposure readings of the scanned photographs into equivalent sound frequencies, each at particular chords and octaves. Take us through the process of creating this soundscape.

As an experiment, I had begun to work with an online synthesizer that helped me scan points within the images and turn the whiter points into higher frequencies of sound at the octaves and in scales that I chose. At times, the images I scanned required specific alterations and manipulations to produce the desired flow of sound frequencies. I wanted to try and extract sounds that would reflect a state of being that I had felt at the time of making the image. In the end, eight sound extractions out of eight images were stitched together to form a three-movement sound piece, a sort of a sonata.

What about this relationship between images and sound excites you the most?

It’s not necessarily a relationship between images and sound that specifically excites me. Today, I don’t think in terms of photographs but more in terms of images. The images could be still, they could be moving, they could be text or sound. The possibilities of the image are infinite. The sound extractions that I made were just me trying to stretch my own images into another form. So what excites me is still the image itself; the relationship between image and sound is just a tiny part of it.

In the early days of your career, you challenged the materiality of photography by developing roles of film in different solutions and making cameras out of cardboard. Do you still feel the need to push the boundaries of the medium?

I think you have to keep challenging yourself otherwise you are dead or irrelevant. In the beginning, this was through the materiality of the medium for me, later it became about the narrative engine of the work. How I challenge myself keeps changing and it’s something that always needs to be there.

Previously, you’ve spoken about how your work is steeped in doubt. Is that fear or uncertainty still as much a part of your craft as it used to be?

I don’t care so much about the craft. What matters to me more is the position I take with the craft. And yes, I’m always scared about whatever it is that I’m trying to do because it’s new to me each time.

What are you currently working on?

I’m now trying to grow back some hair on my head.

The project was celebrated at the Oberhausen International Short Film Festival, Arkipel in Jakarta and later traveled to the International Film Festivals at Moscow and Vancouver.

All Image Courtesy: Sohrab Hura/Experimenter, Kolkata.

Text by Ritupriya Basu.