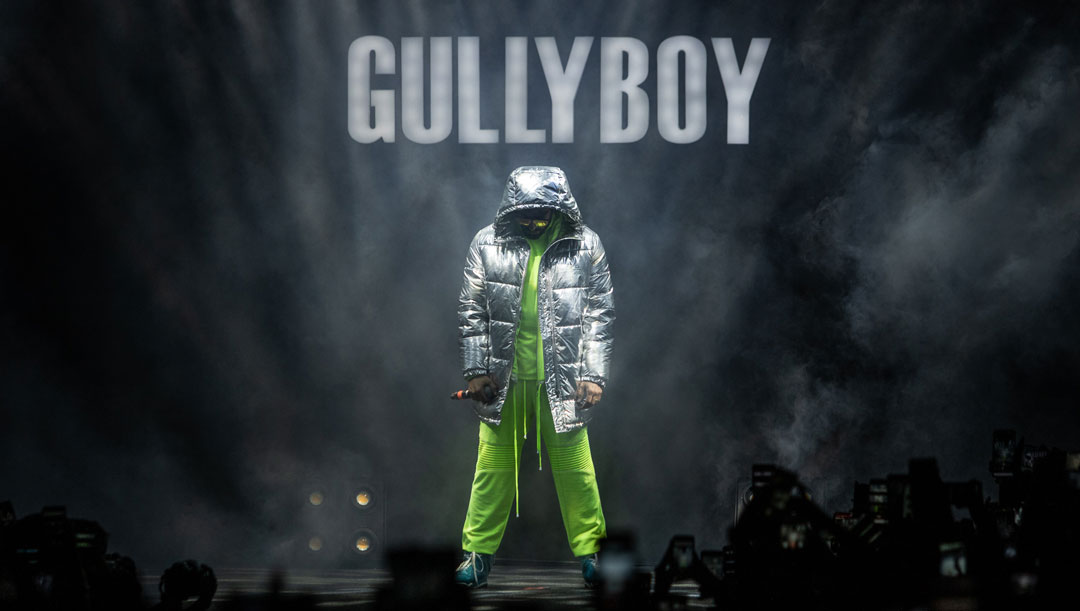

The hip hop scene in India comes to global attention with the Berlin premiere of Zoya Akhtar’s Gully Boy. Director of the Toronto International Film Festival, Cameron Bailey tweeted on never hearing louder applause for any other film in his 20 years of attending the Berlinale. Although directed by Akhtar, the film, which features the work of Indian rappers Divine and Naezy, is already infused with the sense of being significant in a larger series of temporal shifts within the hip hop scene in India. Interestingly, even before its release, it already comes with the larger cultural sense of somehow belonging to the community it represents. Contributive to this aspect is the fact that it was made by Akhtar by actively interacting with the rappers, their circumstances, and following the hip hop scene in India. However, a much larger clue would probably be the subsequent interviews with the rappers Divine and Naezy, who speak of an affinity to the film, and a firm belief in the global future and representation of Mumbai rap across India and the world.

Inspired by the lives of Divine and Naezy themselves, Gully Boy is the story of Murad, the son of two working-class parents in Mumbai, who discovers his talent and passion for rap and enters the hip hop scene of his city to speak about the struggle of politics, living in the chawl and discovering the space of hip hop to speak about self-representation. It is this, perhaps, that makes the connection with the lives of Divine and Naezy themselves, who grew up in JB Nagar and Kurla respectively, and first came to wide attention in 2014-15 with Aafat and Meri Gully Mein, DIY videos to fantastic songs shot on a shoestring budget.

A number of critics, including Tej Brar, founder of Third Culture Entertainment and Ex Artist Manager at Only Much Louder (one of India’s largest new media platforms. Brar also signed Naezy after Aafat.) have drawn parallels to the emergence of ‘real’ Indian hip hop and the birth of hip hop in New York.

Indeed, it is not wrong to relate the articulation of a common experience of marginalization, and unarticulated political unrest finding its fruition in the artistic form of hip hop, which originated in the post-industrial Bronx in the 1970s, primarily among African American and Latino youngsters of ghettoized spaces and lower income households. What is interesting in the music that India’s new rappers make is this extremely conscious proclamation of identity and space and the linguistic politics of regional identity.

The frequent use of the word ‘Gully’ in Divine and Naezy’s music, wherein they extol the talent, ambition and lives in the Gully, along with the video to Meri Gully Mein point to the same.The cultural equivalent, if one were to search for it, would probably be the ‘street’ in American hip hop. Easy as these equivalents are if one were to make them, the use of the word Gully invariably leads to some other questions, and perhaps the first place to look would be the title of Akhtar’s movie: Gully Boy.

An interesting choice; it points to the intersection of a number of debates. Divine and Naezy rap primarily in Mumbaikar Hindi, and are proud of doing so. In using the words ‘Gully’ and ‘Boy’ together, the movie is responding to a number of contestations. The first, of course, is reclaiming the word ‘Gully’ as a space of creative performance, political protest and an active, brimming energy. The second is an anglicization of the phrase ‘Gully ka ladka’ as a pejorative, often class-based insult, to the effect of turning it around to being the central locus of a Hindi/English debate. English, in many parts of India, often becomes the ticket to an entry to exclusivity, class, caste and region based. The use of the word ‘Boy’ brings this to light, standing out almost in juxtaposition to the other half of the title.

The movie itself is highly contextual in its regional dynamics, of course, and reflects only a Mumbai-based response to the wide variety of hip hop trends across the country. This is only to be expected in a country that receives its introduction to hip hop through Punjabi-English star Baba Sehgal, along with the rich reception that global stars like Akon and 50 Cent got iin India in the early 2000s, rappers which notably influenced Naezy and Divine in their introduction to hip hop.

A trajectory of influence in hip hop across India, however, would be incredibly hard to draw. A recent series, Hip Hop Homeland, by 101 India points to the same, with rappers across India bringing their talents to the forum. From the North East, we saw Feyago, Khasi Bloodz, the Symphonic Movement, and the Cryptographik Street Poets rapping about their struggles vis a vis the marginalization of the North East, politically, as well as its artistic exclusion from the larger hip hop landscape of India. In this, they spoke of the attention rappers like Divine received, while D-mon, an equally good rapper, received next to none from the mainland. A number of other rap artists across India, such as down south in Kerala, include Street Academics who are an alternative hip-hop group. Hiphop Tamizha from Coimbatore in Tamil Nadu are often credited with beginning Tamil rap as a genre.

Even within Mumbai, a number of rappers and crews remain unrecognized, silently a part of producing the “scene” in the city.

Thus, the hip hop scene in India has tumultuous regional baggage to accommodate, and a single article cannot hope to do justice to its numerous specificities. The release of Gully Boy, however, opens up to global attention the ever-evolving creative landscape of hip hop in India and promises to be a much-needed musical treat.

All photos by Vriddhi Sawlani.

Text by Anandita Thakur.