Contemporary fashion, media and art’s centering of fat female bodies suggests the phenomenon’s first appearance to be during feminism’s fourth wave body positivity movement. But a look at art history, especially the nudes, reveals the once casual placement of the average female form in all settings.

As the mother feeding the child, the goddess taking a bath, the woman as an athlete, the numerous odalisques, all scattered over cultures. What makes this antiquated placement of the ‘heavy’, ‘natural’, never-seen-a-gym woman more radical than their visual representation today? Think of it in analogies.

Once an all woman panel is as common and not eyebrow-raising as an all men panel and it can exist without being performative, women’s empowerment tokenism, then, and only then, one can relax and believe the sought out equality has prevailed. It is the same for ample bodies in visual culture. Today the ideological standardization is a woman curvy in the ‘right’ places with taught abs and muscles. Against this exists the 30000 years old sculptures of the Venus of Willendorf, Venus of Laussel and the Venus of Lespugue.

The fleshy cheeks, double chins, flabby arms, love handles, protruding bellies are not a celebration of the thing itself, the fat, rather the woman as she is. The woman, her broad breasts and pelvis, taken for granted as life’s simple fact, as simple as the grass beneath one’s feet. The emphasis is not on the physique or on its ‘deviation’ from the standard. There is no standard to begin with and that is radical in its directness.

The ancient hands which lovingly carved these forms were engaged in an act of somatic representation, while much of what we see today, the roundabout manner of celebrating the woman’s thick body, inherent in which is the baggage of criticism of the same body, is somatic but psychologically. Meaning, it begins in the mind before it settles on the body. An argument has to be made, and won, before perception of such a body can give joy.

‘Realord‘ from the series New Providence

Oil on Digital canvas,

8.25 in x 10.75 in

2022

Tanya Chaturvedi

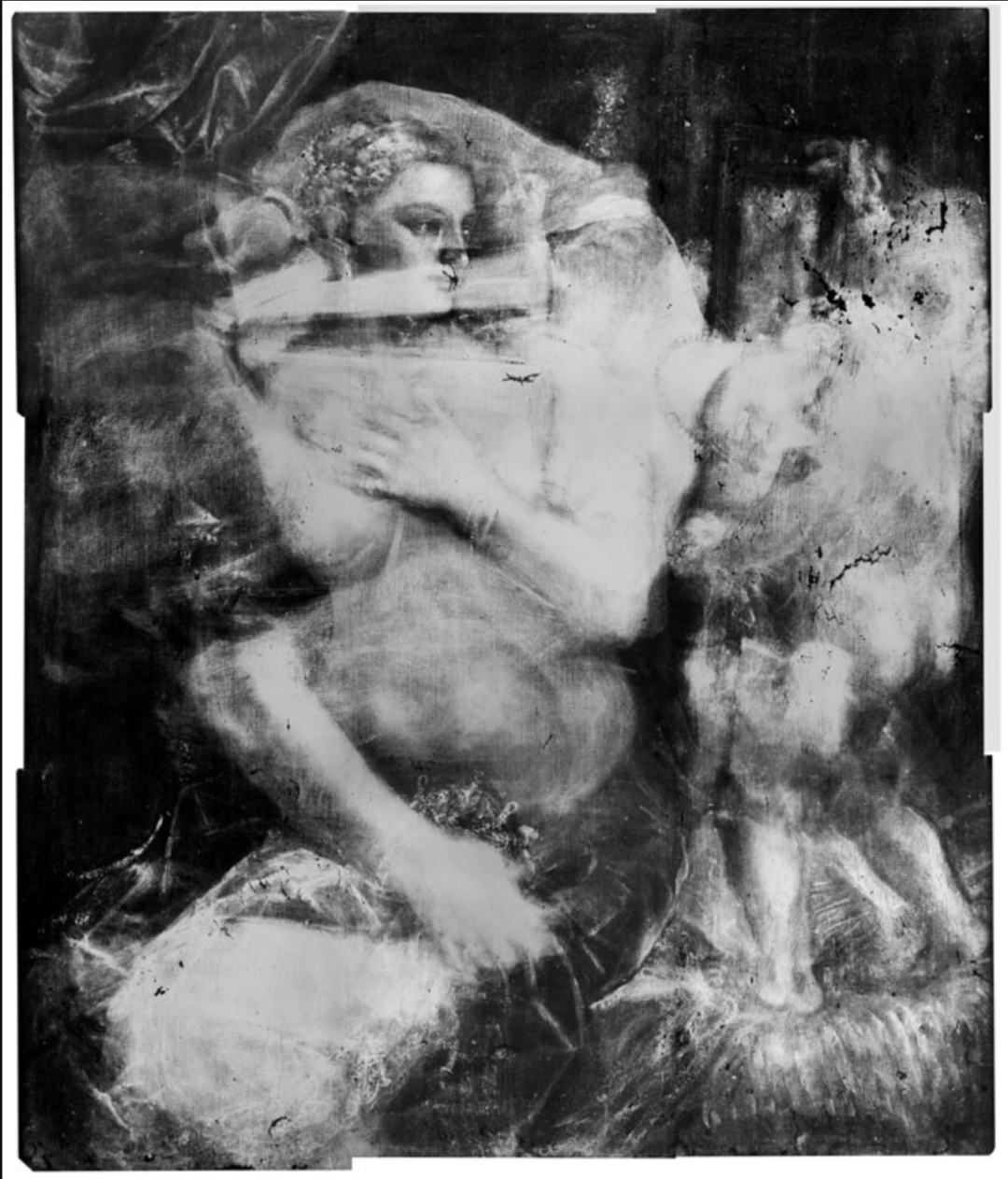

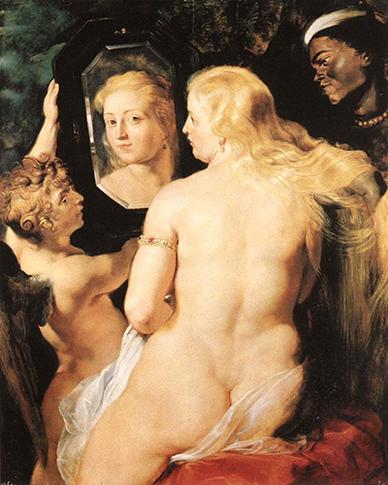

Peter Paul Rubens Venus by the Mirror

Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640), the Flemish artist, was one such connoisseur capturing the mellow beauty of flesh. Not flesh ashamed of hanging from the bone, but soft, dimpled, asymmetrical and endearing.

His The Three Graces (1635) and the twenty portraits in the Marie de Medici Cycle (1621) unabashedly display the form without making fatness their primary point of engagement. The Medici cycle was commissioned by the patron Medici family and contains no attempt on the muse’s or the artist’s part to airbrush, Photoshop or filter the ‘flaws’. His Venus Before Mirror (1613) and Venus Wounded by a Thorn (1600) are similarly captivating.

The liberating aspect being that his contemporary audience would have discussed brush strokes, technique and light before considering the proportions of the body. He was deeply influenced by the work of Titian Vicelli (1490-1576), whose Woman with a Mirror (1515), presents similar style. In modern art Pablo Picasso’s (1881-1973) Female Nude Sitting with her Legs Closed (1906) and Lying Naked Woman (1955) are good examples along with Henri Matisse’s (1869-1954) numerous Odalisques. The German painter Paula Modersohn-Becker’s (1876-1907) Reclining Mother with Child (1906) is a work which in its abandonment and simple tenderness exposes the triviality of most modern campaigns celebrating motherhood and the raw physicality of the experience. Bob Martin’s Serena (2004), a photograph of the athlete, is another stand out moment not just in sports history but the history of capturing women’s bodies.

The picture reproduces the surprising fluidity of the ular body, its force and femininity and triggers a recalibration of what evokes admiration for the female form in modern culture. It is a photograph challenging the viewer’s gender, racial, aesthetic and popular culture programming.

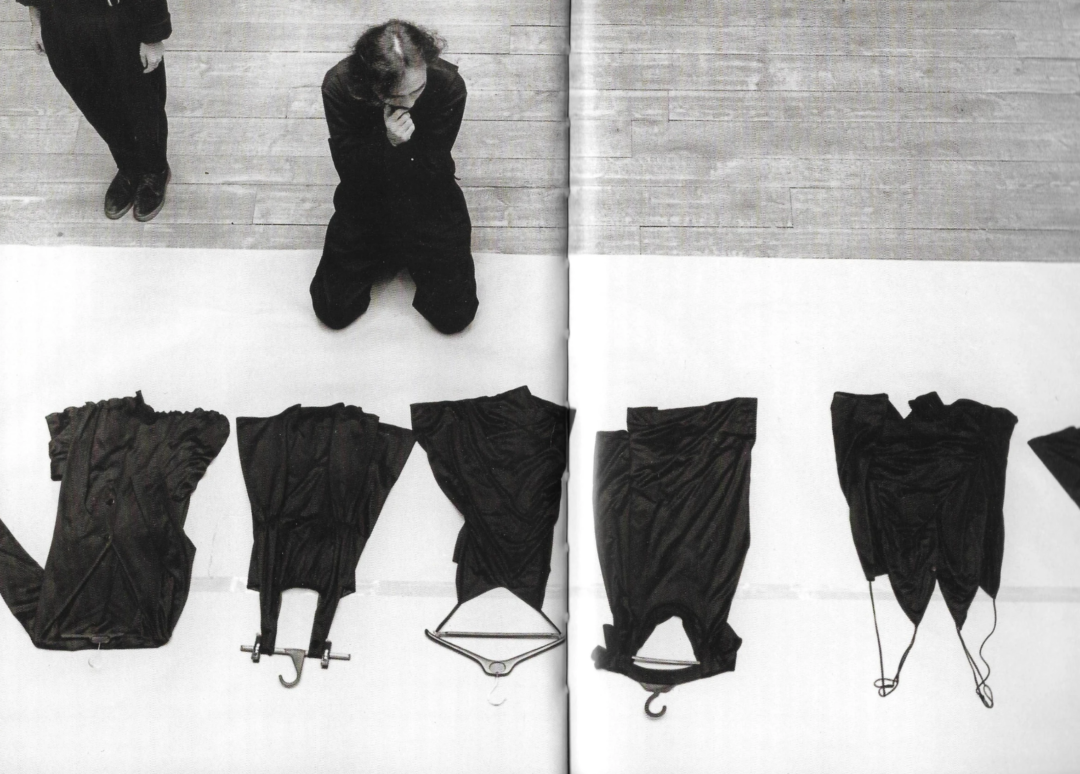

‘Yohji Yamamoto Memories’

Archives

1997

Another instance of immediate perception translating to joy of ‘big’ women can be located in the sculptures of Niki de Saint Phalle (1930-2002). She was a French-American sculptor, painter, film maker and book illustrator.

She sculpted her own version of The Three Graces (1999), voluptuous, in joyous movement and almost challenging the average viewer to dare comment upon the body. One does not comment, saturated as they are by the color, celebration and primitive innocence of the style. It is almost a visualization of the spirit via the body. Yet the description of her art as ‘larger than life’ in common art commentary beats the purpose. It again makes big bodies occupying everyday spaces as something removed from reality.

Her sculptures with thick arms, bellies, legs, busts and bottoms occupy many streets and gardens from America to France. She called them Nanas. Her stylistic choice is interesting since she used to be a fashion model before quitting the industry. Her form was slight and small and one wonders if she via her Nanas was attempting to occupy more space in the world; for her own self and on behalf of all women containing, disciplining and shrinking the body. Her Tarot Garden in Tuscany (1998) is a testament to the scale, metaphorical and literal, of her vision. She lived for years within one of the giant sculptures The Empress, a sphinx.

The structures which one can enter and leave bring to mind certain Russian Virgin Mary sculptures which would double as shrines. They would open at Mary’s chest to reveal compartments containing divinities. All of these works, intertwining over the ages, regarding the female body and its overt and covert messaging, are the bedrock of modern visual culture.

NFT inspired by Venus figurine;

Imagining documenting of new history

There is a thread of commonality between Phalles and the ancient style. It is not presuming to be transgressive even if it ends up transgressing against established norms. Transgression is of two kinds, the audacious and the apologetic. Fat as transgressive inevitably bottles up the idea within these two, narrow domains.

In the world of fashion this understanding of ‘plus size’ as path breaking, as a challenge to the ‘genre’ has had dire results. Especially for Indian designers of old repute who are only recently waking up to the ‘trend’. Unless the comprehension of the body, of all bodies as participants in discourse of culture germinates organically, in the consciousness, in the very belief system of designers, the results will be superficial, disappointing and in worst cases horrendous. Sadly the recent Cannes looks by Aishwarya Rai Bacchan come to mind.

There is a tragic quality to the downfall but in every tragedy there is a ‘rise from the ashes’ hope. The woman has been made to embody a Dickensian heroine whose glorious past and decaying present are hard to look away from. A cursory glance can tell one that as long as she fit the ideological standards for how ‘heavy’ even heavy women can be, she was beautifully styled. But once she crossed that arbitrary threshold designers did not know what to do for her.

Her designers, Falguni and Shane Peacock are notorious for their views on plus size women. Falguni drew a lot of flak for asking heavy brides and potential clients to lose weight before their wedding and advising them against deep cut blouses. Only in 2017 was she recorded as saying that plus sizes cannot be ignored. These kinds of thoughtless, rushed, haphazard attempts to jump on the inclusivity bandwagon result in debacles like the one at Youthforia, a cosmetic company, whose lazy attempt to ‘seem’ to cater to all skin shades led to the darkest foundation formula being literally black pigment and nothing else.

So which designers should one make heroes out of? Big money is clearly not translating to good fashion. Can we force Aishwarya Rai to carry the body representation movement? Or should she just be beautifully styled for the carpet without it being about weight? Such seamless progressiveness is completely absent in our culture. A good thumb of rule, as far as stylists are concerned, should be to stay away from advice which advocates ‘distraction’ from all that is ‘wrong’ with one’s body; height, weight, complexion, whatever. It only makes insecurities, personal and taught by culture, painfully evident. On the same red carpet, was the elegant and beautifully styled Lily Gladstone. Netflix’s Bridgerton actress Nicola Coughan is another red carpet stunner. The failed attempts to hide under gaudy, billowy fabric, colour and print only exposes hatred of a certain kind of female body in the South Asian fashion industry. Attempts to set things right are underway, have been underway for a long time in India. There was the tokenistic 2019 Lakme Fashion Week special plus size show and more concretely the Ministry of India Textiles size chart commissioned in the same year 2019. But the former’s impact, if any, faded out and the latter is still under works. On the International front, Indian origin designers show more promise, Gaurav Gupta’s look for Lizzo in 2022 is a moment for the books.

The direct engagement with the female body in painting and sculpture disappeared with the advent of modernist and abstract art styles. The consumption of it now relies solely on photography, film, fashion and red carpets. In celebrity fashion particularly, the body, just as much as the cloth draping it, is in dialogue with the audience. Earlier, when life expectancies were low and female mortality was much high due to childbirth, fat was associated with good health. It was, beautiful, inviting and promising.

Its representation echoed this. Fat women meant that the areas they belonged to were fertile, rich in fruit and livestock. Today fat female bodies are not joyous but funny, not serious but ridiculous. The thin bodies which would distress earlier now are pleasing, especially when beheld virtually. It is not common sense but slow perversion. Even the sexually curious gaze categorizes the voluptuous body as active and initiating; while the thin as passive and inviting. Over the ages the polysemy of ‘fat’ has only increased. Today body fat has become a costume in itself; most who wear it are outrageous. Just as the sculptures and paintings of past give a slice of reality so will these costumes of today. They are cultural archives recording something which written reports, history narratives and even videos cannot. As far as perception of fat bodies is considered, maybe this is the age of agonism and at its end relief awaits.