In a dimly lit studio in New Delhi, Palak Modi forges a visual language shaped as much by intuition as it is by discipline. To step into her work is to be drawn into a field of tension—between decay and tenderness, silence and saturation. Modi calls her studio both a sanctuary and a battlefield. That duality is key to understanding her practice: it is a space where she falls apart and rebuilds, where control dissolves and instinct quietly takes over.

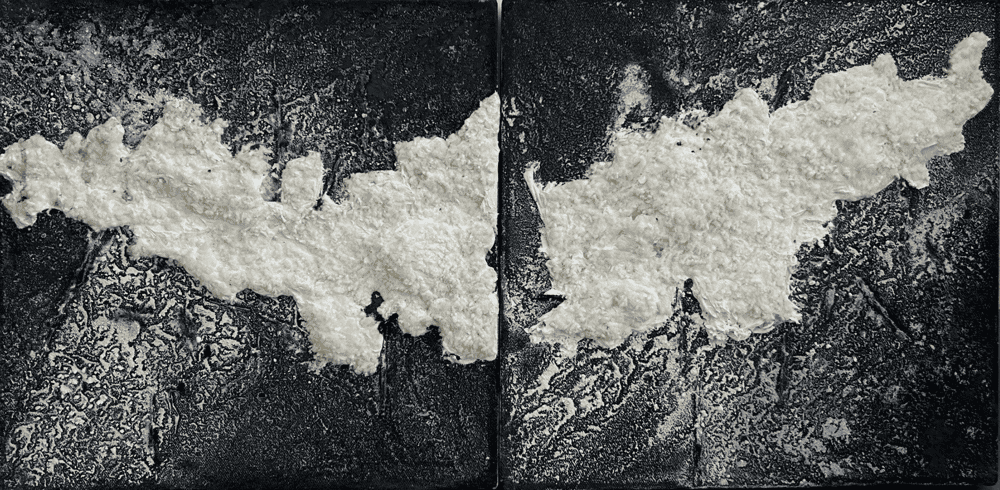

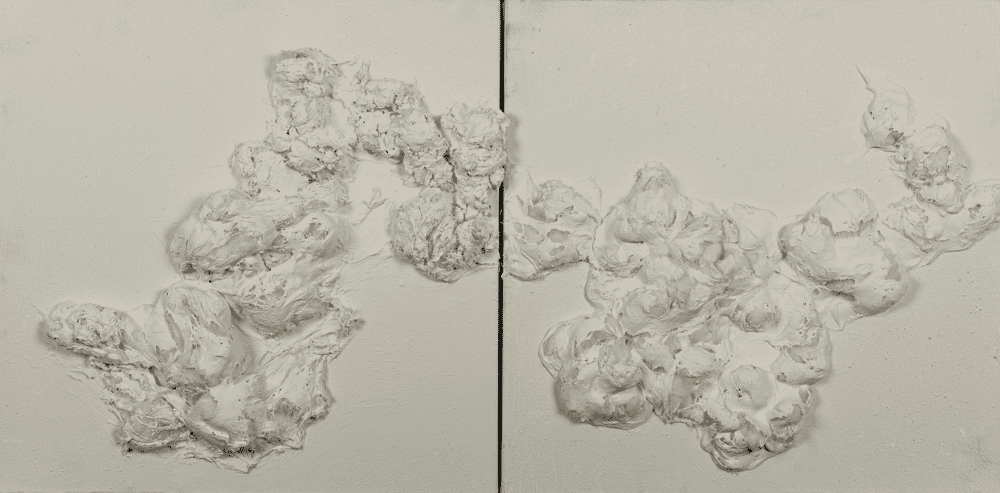

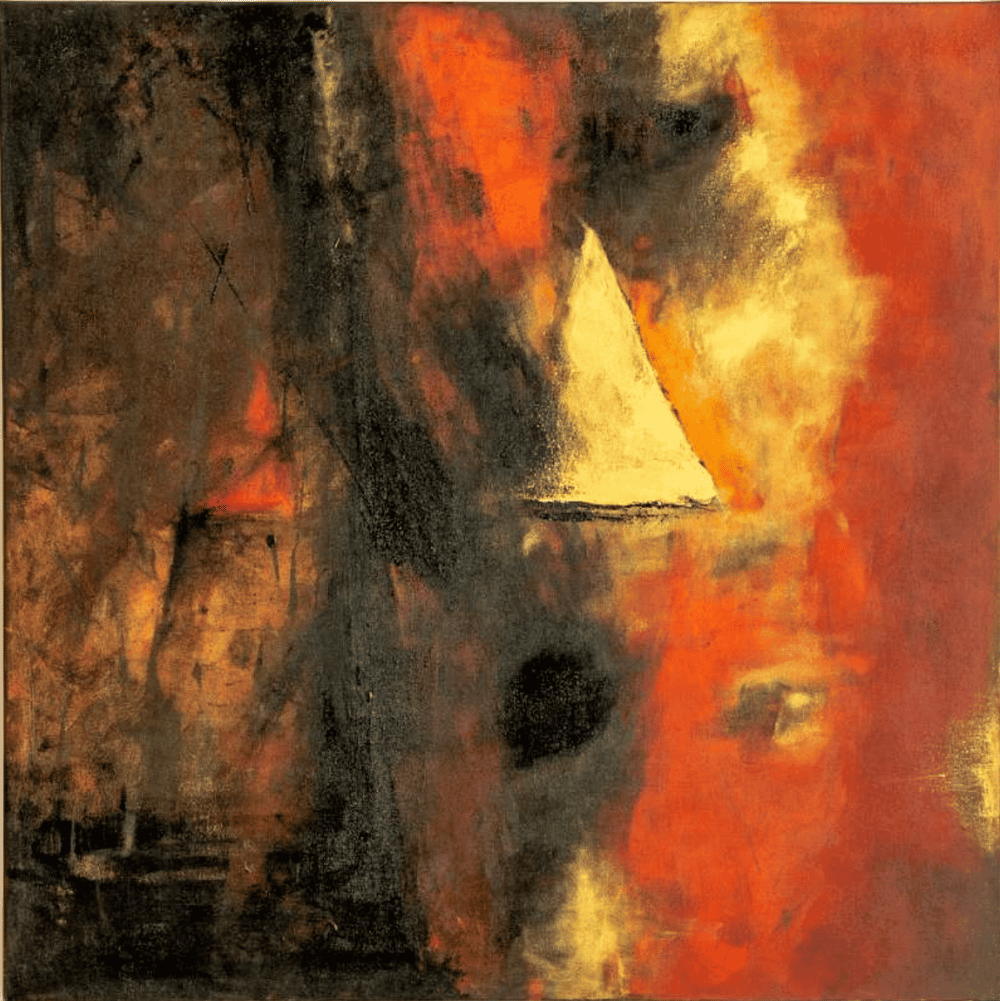

Modi’s surfaces are neither flat nor polished; they are wounded, layered, and repeatedly unsettled. Her compositions often feature scorched muslin, oxidised metal, mineral pigments, and found detritus—materials that come with their own history of wear. She gravitates toward what she calls “things that have already lived a life.” These fragments resist manipulation, and in doing so, lend the work a raw honesty. The unpredictability of the material is not a limitation but an active collaborator.

Much of Modi’s work appears minimal at first glance, but it resists easy categorisation. The quiet aesthetic belies an emotional undercurrent that is often dense and unresolved. Her use of restraint is neither ornamental nor detached—it is emotive, often aching. Whether it’s the subtle folds in cloth sealed beneath lime, or the barely-there washes of ink bleeding into cement, her work speaks in murmurs. But what it says is unforgettable.

Her series of small-scale panels and mixed-media works reveal an obsession with surface tension and psychic residue. The patina of time is central to her aesthetic; she doesn’t paint over history, she excavates it. Viewers are often made to slow down, to come close, to sit with the discomfort of ambiguity. Her forms hover between abstraction and ruin, evoking, as one critic notes, “an intimacy with the act of undoing.”

Palak’s process is both visible and invisible. She builds surfaces only to tear them down. There are things buried beneath pigment—a torn letter, a loose thread, a memory—that never fully emerge. Her compositions feel less like final statements and more like weather systems: forming, dissolving, revealing only what they must. Every layer negotiates the fragile balance between knowing and not knowing, between saying and staying silent.

Cinema plays a role too—not in subject matter, but in the emotional pacing of her work. Films, especially those rooted in slow, observational storytelling, serve as a salve for creative blocks and as a map for atmospheric construction. The stillness of Tarkovsky, the interiority of Wong Kar-Wai, the texture of Indian regional cinema—these seep into her practice.

Care and fragility are not afterthoughts in Modi’s work; they are its foundations. “Even the most fragile parts deserve to exist without being forced into strength,” she says. Her compositions hold space for hesitation, for bruised edges, for the near-invisible. In doing so, she carves a place for vulnerability not as a defect, but as a deep kind of wisdom.

What makes Modi’s work so affecting is not that it offers resolution, but that it makes space for fracture. Her panels speak of ghosts and remnants, of what cannot be said but insists on being felt. In her hands, stillness becomes a form of resistance, and decay becomes a kind of grace. This is not art that asks to be admired. It asks to be witnessed.