The concept of the mohalla in Northern India has been the subject of many beautifully framed cultural ethnographies across India and the world. Linguistically, the word travels far and wide, with Persian origins, but with equivalent meanings in Russia, India, Pakistan, and much of South Asia. If translated, the closest one would come is the word ‘neighbourhood’. Any speaker of Hindustani would tell you, however, that the sense of community closeness and interspersed, narrow-laned living that the original word bears does not come through in the translation. Mohalla, as a concept and space, is now a hauntology between translations and memory. As urbanity moves with a throttling forward thrust, it becomes easier to forget the lived cultural memory of this space, increasingly replaced by newer cookie-cutter versions of high-rise community housing.

In India Habitat Centre, currently (5th-8th February, Open Palm Court) is an exhibition dedicated to preserving the cultural memory of the mohalla as an entity, remembered by its older denizens and inhabitants.

Sometimes recalled with a fondness for the sense of a closeness that urban space simply cannot conceptualize anymore, and other times in the sadder vein of endless municipal reconstructions, post-liberalization and a thousand high-rises popping up seemingly overnight: these are the considerations we must remember when we enter Kavita Dixit’s Mohalla.

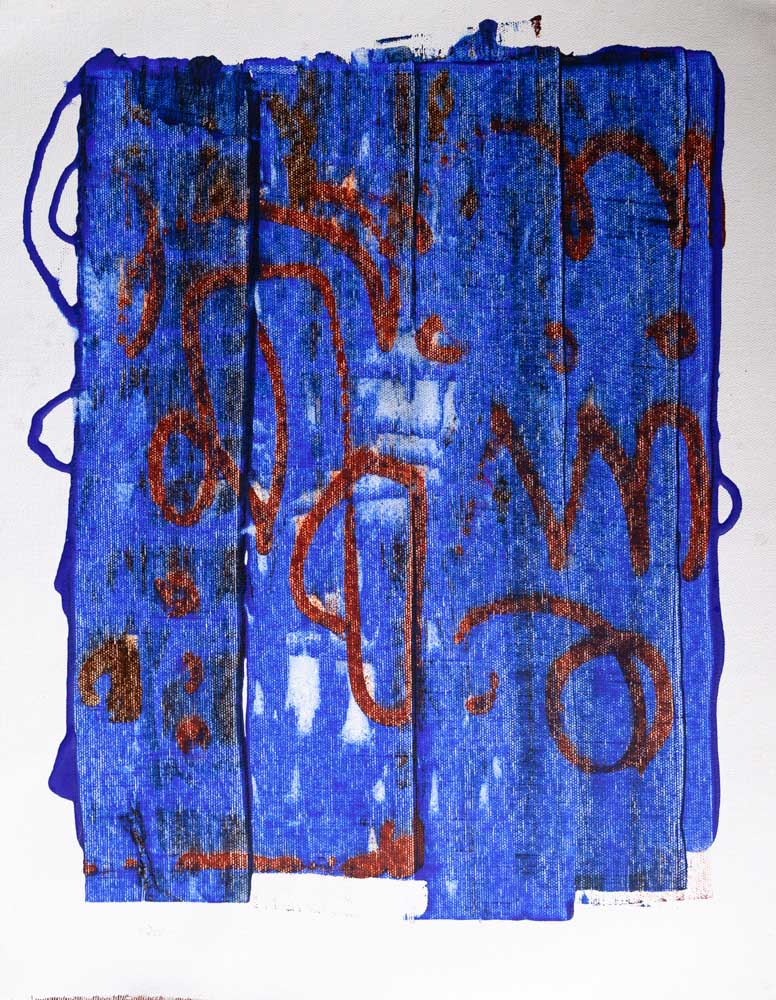

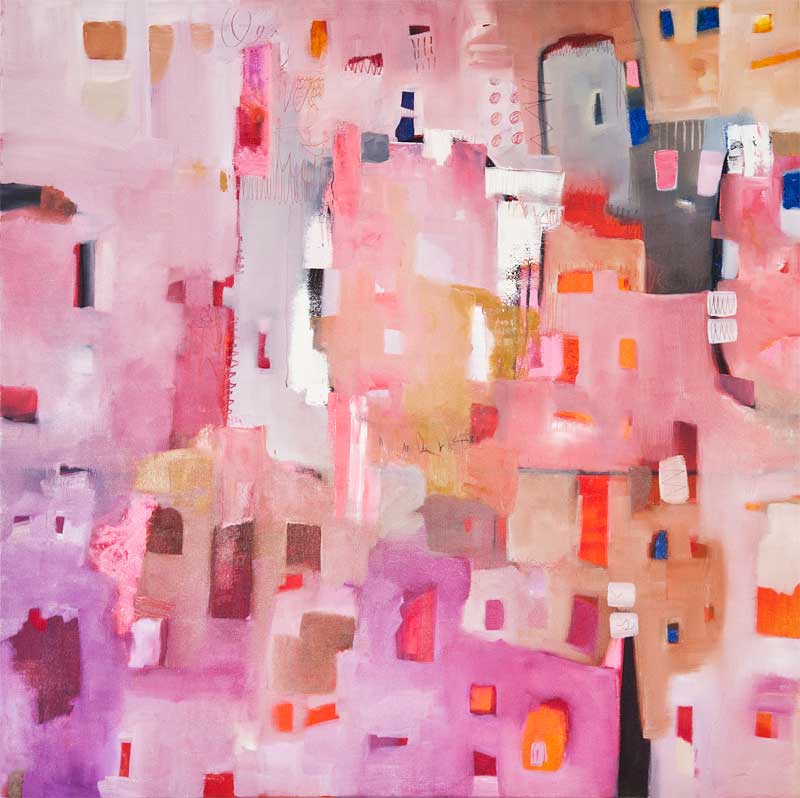

The series is presented to us as a variety of abstract and semi-abstract paintings. One observes a vigorous, bright tonality. At times, in certain paintings of the series, there is a sense of various buildings almost merging into one another, and yet the effect does not betray a sense of cramped claustrophobia, as much as an organic fusion between the buildings; much like trees.

Of the bright colours, Dixit says she was inspired by the mohallas of her childhood, and the ones she’s observed travelling across the country: their walls are always differently coloured, dynamic and alive, changing hues as one travels to different parts: thus, darker shades of rouge and brown emerge closer South, while in the Western parts of India, one observes bluer tones.

When asked about what struck her, artistically, about the mohalla, the artist emphasises the busy rhythm of them. Thus, a number of houses she paints in the series have a closely 3-Dimensional quality to them, buildings that are defined, but not defined solely, always against other buildings. Within these, she accommodates lanes and staircases, and bylanes. In this, there is an interesting liveliness to the work: one can almost hear the buzz of bodies, and conversations drifting in and out of the buildings.

Dixit speaks of her childhood: months spent at her grandparent’s house in Nawanshahr, Punjab, where the mohalla came alive in similar ways. An organic connectivity defined the lives of people, she recalls:

There would be a vegetable seller coming with his wares every evening, women congregated with their children, on one end there would be papads being sold, on the other, dupattas. It struck me when I began to think of Mohalla, how many of our chores we do alone, living in ‘urban’ cities. The sense of personal space, geographically and spatially, has become very important, but people still miss something. The role of community space is ignored completely- the idea of the angan, for example, does not exist anymore. Mohalla struck a chord with everyone I spoke to about it.

Dixit has had a wide and diverse career, beginning as a producer for television, at CNN in Atlanta. Over the years, she has worked with a variety of mediums- film, photography, design and print- she now heads Red Design Company, her own graphic design studio, out of Delhi. Of her choice of medium in Mohalla, which is primarily oil paints, she confirms it being instinctive. The richness of oil, its texture and how much it lends itself to artistic manipulation makes it an appropriate choice for the series, which Dixit reports required a large amount of removal, etching and drawing-over.

Theorist Mark Fisher speaks of living in the postmodern world as a keen sadness: the sense of always being caught somewhere between connected loneliness and distracted boredom. Visiting Dixit’s Mohalla is almost a suspension of time and history: viewing the paintings, one stands with the keen awareness of a bygone space, but is simultaneously infused with the bright beauty of its world, and time begins to ebb slower. Conveyed to you through wistfully playful oil based tones, Mohalla strikes an inter-generational chord that cannot be ignored.

All paintings by Kavita Dixit.

Text by Anandita Thakur.