Bharat Choudhary a teacher, and an independent photographer based in London, has documented the lives of people in such a magnificent way, that viewers are bound to take a step back and wonder about the details of those featured in his photos. Bharat grew up in Nigeria and later moved to India where he studied at the Indian Institute of Forestry Management.

He worked with CARE International in India for five years before moving to photography. He was mentored by Raghu Rai (Magnum Photos) and Nitin Rai at the Sri Aurobindo Center for Arts in New Delhi. He further studied at the University of Missouri, USA, from where he graduated with a MA in Journalism. Since 2011, he has been documenting issues of Islamophobia and the racialization of Muslim communities in America, England, and France.

This is our conversation with him, about his early career, ongoing and past projects, and his love for all things art.

Tell us about yourself, your career as a photographer/Your journey as a photographer

My father was an engineer working in different countries in Africa. I grew up in Nigeria. My father was an avid wildlife photographer and had two big boxes full of cameras, lenses, filters, and whatnot. Our bathroom was his darkroom. Once in a while I was allowed to use his cameras and take some photographs. On weekends, we used to drive to Badagry beach in my father’s 1976 VW Beetle. We had a great time in Nigeria.

As a teenager, I returned to India. I studied at the Indian Institute of Forestry Management in Bhopal. After my education, I started working with CARE International on several rural development projects in different parts of India. That is when I was introduced to the field of development communication. But after 5 years, I grew tired of my 9 to 5 job. And then one day, I still don’t know why, my father gave me two of his beloved cameras; an Asahi Pentax K2 and a Minolta X-700. I felt like photography set me free and I knew that this is what I would like to do for a long time.

But I wanted to formally study and learn photography. I approached Raghu Rai to see if I could become his assistant. I was informed that he and his son, Nitin Rai, would soon begin teaching at the Sri Aurobindo Centre for Arts and Communication in Delhi. I left my job in Gujarat and arrived in Delhi to study photography. Around the same time, I was awarded the Ford Foundation International Fellowship. It was a fellowship that would bear my education and living expenses for a course of my choice in any university anywhere. As soon as I completed my course at the Sri Aurobindo Centre, I left for the University of Missouri in the US to pursue a Masters in Photojournalism.

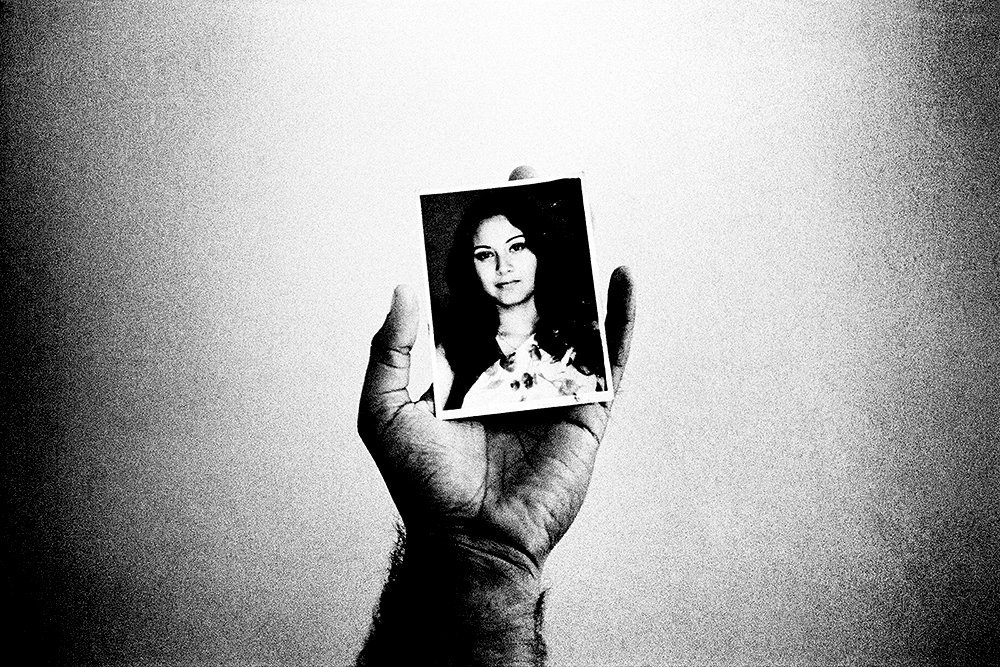

After my graduation in the US, since 2011, I have been documenting issues of cultural imperialism, Islamophobia, and the racialization of Muslim communities in America, England, and France. My work has been supported by a number of grants and awards. I have been a recipient of the Alexia Foundation Professional Grant and the Getty Images Grant for Editorial Photography. I have thrice been a finalist for the W. Eugene Smith Grant. I was also a finalist for the Aftermath Grant and the Philip Jones Griffiths Award. I was a jury member for the 9th China International Press Photo Competition. My work has been published in TIME, NY Times, Le Monde, International Herald Tribune, The National, Neue Zürcher Zeitung, La Repubblica, Philosophie, and the Sunday Times Magazine, including others. My photographic projects have been exhibited at several spaces including Getty Images Gallery, London; Dali International Photography Exhibition, China; Pingyao International Photography Festival, China; Delhi Photo Festival; Open Society Institute/Moving Walls, New York; Obscura Festival, Malaysia; LOOK3 Festival, Virginia, USA; LUMIX Festival for Young Photojournalism, Hannover, Germany and The Gallery, British Council, New Delhi.

What was the first-ever project that you pursued as a documentary photographer?

My work in India when I was a student could be considered as the first ‘project’ where I photographed with a documentary approach. As a person, I have always been fascinated with the subject of spirituality and religion. So when I began to photograph, I was attracted to India’s religious pluralism and syncretism. But simultaneously, I was also disturbed by conflicts that often erupt between India’s many religious communities. After some time, I observed that the project was beginning to develop as a commentary on the spiritual, social and political influence of religion on India and its citizens, and how the idea of religion is so intricately woven in the lives of us Indians. It wasn’t a strategic decision; I think it was more of organic evolution of my own emotions, understanding and perspective.

Most photographers are either inspired by an incident or a person to pursue photography professionally. What was it for you, that made you decide to become a photographer?

I was very interested in photography and in 2007, I had started contemplating to pursue it as a career. I was living in Ahmedabad at that time and had gone to a Crosswords Bookstore with a friend. While she was looking for her books, I saw this book on the Taj Mahal by Raghu Rai. I did not know who Raghu Rai was nor had I ever taken an interest in any photo book. But that book was something different. I was amazed to see how someone could photograph the Taj Mahal in so many different ways, seasons, lights, and colors. I had been to the Taj Mahal a few times but that book made me feel that I might have been to the Taj Mahal, but I had never seen it before. I went home and tried to read more about Raghu Rai. After looking at his work continuously for a few weeks, I grew certain that I wanted to become a photographer, and that he has to be my teacher.

Which projects do you fondly remember working on?

In 2016, I had injured my spinal cord (which still hasn’t healed) during an accident. The accident happened just a week before I was to leave for Srinagar to begin work on a new project. My injury left me severely depressed; I was bed-ridden for 13 weeks and had lost all hope of walking again. But then one day I decided that I just can’t go on lying on a patient’s bed anymore. I had to move out of that zone of physical and mental impairment. Against my family’s wishes, I managed to fly to Srinagar. Showkat Nanda, Sharafat Ali, and Izhar Ali, my dear friends (read brothers), hosted me at their place and took such good care of me that I was walking again in just a week’s time. I spent around three months in Kashmir. What I saw in Kashmir completely transformed my understanding and opinion on subjects like nations, citizenry, democracy, wars, conflicts, politics, and humanity. It is in Kashmir where you realize what pain and suffering really mean. I have never seen so much darkness and depression anywhere else in the world. And nowhere else have I seen such beautiful and resolute human beings pushing on in spite of all the pain that they carry inside. In Kashmir, celebrations are like mourning, and funerals are like celebrations. I was barred from publishing my work from Kashmir for security and political reasons. But the people that I met in Kashmir, the stories that I heard, the extremely frightening experiences that I had, and the love and care that I received from Kashmiris are forever going to remind me of my responsibilities as a photographer and as a human being.

What are your other interests besides photography?

Cinema, music, and poetry. I am a cinephile; I try to watch at least 3 movies (World Cinema) in a week. Cinema keeps me sane in this mad world. I am also re-learning the guitar. And whenever I want to return to myself and fall in love with life again, I read poetry.

Are there any other forms of art that you practice?

Writing poetry and singing. But I wouldn’t really call them ‘practicing an art form’. They are more like what I enjoy doing when I am not photographing, watching a movie, reading, teaching, or cooking.

How would you define your genre of photography? Who is it inspired by?

I see myself just as a photographer and resist all labels, like a photojournalist, documentary, or conceptual photographer. And that has been the case always. Because most of these tags or labels are just cages that the market defines for its own convenience. The genres or labels are then used to tame you and to force you to stick to the market’s stereotypical ideas of what is what. But if I try to be objective, I’d say I follow a humanistic approach very much derived from the documentary practice of photography.

Last time we discussed your project based on identities (The Silence of Others), I would like to ask what inspired you to work on it in the first place? Was it a personal experience or an incident that encouraged you to research on the said subject?

My personal experiences in India and abroad have guided my thought process. In spite of our religious diversity, the constant conflict between religious communities, especially the Hindus and Muslims, has always disturbed me. The Babri mosque demolition, the Bombay bombings and riots, the killing of Dr. Graham Staines, the Chamba massacre, the Gujarat riots, the Muzaffarnagar riots and now the anti-Muslim pogrom in New Delhi; all these events have been shaping my life and continue to direct my work. In 2004, I was part of a communal harmony project team in Gujarat that was working with riot-affected Muslim families. The team’s task was to counsel the riot victims and develop plans for their rehabilitation. The sight of young but maimed, raped and paralyzed human beings still haunts me. In 2009, as a student at Missouri University in Columbia, I was once returning to my apartment when a few Caucasian men stopped their truck in front of me and screamed, ‘Osama! Osama!’ They were taunting me. I had a beard at that time. So when the time came to work, I believe, I already had something built inside me that led to The Silence of ‘Others’.

While going through your projects on your website, I noticed that you photograph people who are not used to being photographed, and despite that, all of them appear to be super confident while being in front of the camera. How do you approach people for your projects? Do you have a process that you follow or any steps that you follow that helps you and your subjects get in the zone? It seems as if there’s no distance between you (mental or physical) and your subjects.

Most of my photographs are made after a lot of meticulous planning. I spend a lot of time planning and executing my photographs. I spend weeks and weeks with people at their homes, workplaces, restaurants, streets, trains, and wherever they live or hang out. I am aware of their habits, their schedules, and their work. I spend a lot of time at places where I know my subjects would usually be. Simultaneously, I am always taking note of the light, the surroundings, the colors, and whatever that might make my photograph look interesting. It does not always work out the way I want it to, but I still try to be prepared. Because often, especially in places like Marseille, you cannot just hang around the corner of a street with a camera or move surreptitiously around women wearing hijabs. So, I identify individuals, situations, sketch some possible frames, take some test shots, and spend a few days in advance to know exactly where the right light would be and at what time. It also helps me to be prepared with a plan B. I don’t ask people to fake expressions and even in portraits, I do not direct them. This approach takes a lot of time and it makes my work very slow. Like during my first trip to Marseille, I made just 40 photographs in 6 months. And when I say 40, I mean I actually shot maybe 500 photographs in total in 50 different situations out of which I decided to go with 40 photographs.

But for me, far more important than the skills or strategies, is the human connect that I strive to build with these people. Like, in France, I could barely communicate with the community as I do not speak French and most of them could not speak English. Our communication was largely silent, non-verbal, through gestures or expressions. And through emotions. My objective always has been to get close to people, know more about their lives, and tell their stories honestly. I respect their space, opinions, culture, and do not take their time or emotions for granted. I assure them that in spite of how different I may be from them, I am trying my best to relate to their ‘lived’ experiences and I am thankful to them for allowing me in their homes and lives. And they respect my work. I do not care for photographs at that moment; I do whatever I can to earn their trust and I consider photography as just a process that is enabling us to connect as human beings. I think that is why in most of my photographs, you will not see anything really dramatic or sensational happening. They are just images of their everyday living but in most of them, there is a strong emphasis on emotions to which we all can connect as human beings. You do not have to be an Algerian or Libyan to understand the love a mother has for her child. And you can be from any culture or nationality and still understand the emotions when a young boy wants to hold his girlfriend’s hand for the first time and she shyly pulls her hand back. These and many similar feelings, experiences, and emotions connect all of us together as human beings and that is what I keep looking for in my photography.

You’re a well-traveled and a very experienced photographer, what major differences do you see in cultures and industries across different nations? For example: what major differences do you see between the industry and community in the U.K. and India?

I wish I was knowledgeable enough to answer such a complex question. Here, I can only respond to your question by sharing what I have seen and learnt from living and working – for almost 24 years – in several countries across Africa, the Americas, and Europe. I think cultures everywhere function and evolve predominantly in response to the region’s geography, history, politics and economics. Our socially acquired values, beliefs, and rules of conduct guide our behaviours and they in turn create what we see as differences across cultures. And who we are individually as human beings and collectively as a society – defines our professional behaviours and artistic endeavours.

If I try to speak about what I have observed in the photography community, I’d say there are a lot of differences between us and the West. Photography was invented and practiced in the West much before it reached our shores. So, it is quite natural for them to be ahead of us in some ways – intellectually and aesthetically. But the photography industry in the West is still plagued by a neoliberal mindset and a post-colonial hangover. It most often either refuses to, or is simply unable to, confronts its own prejudice, ignorance, and racism. Like, every year we see so many ignorant racist tropes being awarded in photo competitions. So many photography magazines from the US and Europe repeatedly produce stories that are banal, reductive, and obfuscatory.

Now, one would expect that photographers or the photography community in a country like India would respond to these challenges in a more informed manner and create or support work that originates from India’s highly diverse, complex, and artistically rich heritage and society. But here we too are desperate to seek Western recognition and validation. As a society, our priorities are skewed. All we seek is wealth, fame, and power. We stopped caring about our poor, our socially excluded, our minorities, our elderly, our water, forests, animals, our diversity, our history, and our politics a long time ago. We have started to live a life where the ‘I’ is more important than the ‘We’. We handed our future to the capitalists and now all we have is what is being sold back to us as the ‘live for today’ sickness. We no longer know why we are here, what is our purpose, and where is it that we want to go. We imitate others, we see so much of shallow pretentious work, completely devoid of any meaning, imagination or function, and yet being celebrated as avant-garde. And we confuse popularity with excellence. And this ignorance is so clearly visible in our world of cinema and photography. But in Cinema we still see some promise; there is a group of progressive filmmakers who are really creating amazing Cinema. But when I look at the photography community in India, I wonder where exactly we are headed.

What major discoveries have you made about yourself and your surroundings or lessons that you learned during the course of your career?

Such a wonderful question – a question that requires true introspection and soul-searching. Thanks for asking this!

Before I came to photography, I studied Forestry Management and began my professional career in rural India, along with social workers, activists, and NGOs. My work took me to the remotest and marginalized regions of our country. I cannot even begin to tell you about the kind of poverty and deprivation that I have observed in our country. I learnt how caste discrimination, sectarianism, and misogyny are so deeply ingrained in our every day living. But I also could see how immensely beautiful our country is. The mountains, the waters, the forests, the coasts, the villages; all of it so magnificent that one lifetime is just not enough to experience the beauty of our country.

Photography gave me an opportunity to return to foreign lands and observe several cultures, religions, and communities. It took me to places where I couldn’t have ever been if I wasn’t a photographer. Through photography, I met so many wonderful people and visited such amazing places. I often tell my friends that I have seen sunlight in several countries, but I think there is no light that could ever match the glow and warmth of the sunlight in Southern France. I have seen clear skies but I can’t forget how millions of stars and the moon lit up the night at the Mediterranean Sea while I was on a ship from Marseille to Algeria. I lived in Switzerland for 4 years and it felt like living inside a Ghibli movie with gorgeous mountains, lush green trees, and a sweet wind blowing all the time. I am flooded with so many memories – the hike up to Machu Picchu via the Inca trail, the hike up to a remote mountain top to see the remnants of the original Great Wall of China, observing wildlife in its natural habitat, like the Cheetahs in Namibia, the drive-through Navajo Nation leading up to Monument Valley in Utah, fishing on the Missouri river, and so many more such memories.

But in spite of all these beautiful experiences, everywhere, what always struck me was the similar kind of destitution and neglect of the poor that I had observed in our country. I mean, can you imagine that in the world’s most powerful and rich country, the USA, every night around 600,000 people are homeless without food or shelter. In Missouri, my American friends told me to be scared of no one but the Police. I received similar advice in France. Your skin color can get you killed and forget about justice, no one would even bother to find out who killed you and why. And I am not exaggerating or speaking about isolated incidents. Being a person of colour or an immigrant with a distinct cultural identity, or being someone with no money, can teach you so much – it could actually help you understand the charade of the so-called Western development and liberalism.

Around 10 years ago, when I came to photography, I too had the kind of goals that a lot of young photographers have. I wanted to be able to create images and to attain financial and material success, academic and artistic accomplishments, etc. I used to equate the pursuit of these goals with the purpose of my life. But my travels and experiences have taught me so much about life, and about myself. I have come to realize that there might not be anything wrong in pursuing these goals, but it cannot be the purpose or the real meaning of this life that I have been granted. Science tells us that 95% of our universe is made up of a mysterious, invisible substance called dark matter (25 percent) and a force that repels gravity known as dark energy (70 percent). So, whatever we know about life, or reality, it is nothing but atoms/molecules, which amounts to just 5% of the universe. Can we still say we know everything even when we know nothing about 95% of our universe? Whenever we try to unravel the mysteries of life, there are always two interconnected questions with which we begin. The first is ‘Who am I?’ and the second is ‘What is this world about?’ The first question prods us to explore faith, religion, and spirituality and encourages us to connect with ourselves. The second question leads us to the outside world, our environment, and nature. With photography, I realized that no matter where you begin from; if you wish to seek the answer of one of these questions, you are bound to discover the answer of the other one as well.

The truth is that I had failed to see that my journey was my destination. I did not travel to all these places, or experienced life and nature in its full glory, because eventually, I had to achieve or possess something materialistic or of worldly value. My journeys, my experiences, and the process that encouraged me to question the purpose of my life is what my achievement is. That is what the universe wanted me to understand. That I am not the center of the universe, but that I exist within and among other living things, and that I am just a tiny part of a mystifying concatenation of existence. And if there is anything more that my career as a photographer has taught me, I’d say I now see life as nothing but a journey within. To find out who we truly are, how can we improve, and be happy. And also, to be in love and love more. To love not with a desire to possess or to be loved in return. But to just love.

You have been a photographer for a considerable time. Do you think photographers, photography, and artists have evolved to become better or the authenticity and quality of work that people used to deliver have reduced over the years?

I have not studied much of Art history, but based on whatever little I have seen, I’d say mediocrity was always around. Many of us would love to believe that the quality of work has reduced or artists are not authentic anymore. But I don’t really agree to that. There are so many wonderful photographers and artists who are doing phenomenal work. In my teaching, while we spend a lot of time looking at the works of artists like Robert Frank, Walker Evans, Eugene Smith, Raghu Rai or Dayanita Singh, we also spend a lot of time in understanding works of contemporary artists like Taryn Simon, Laura Letinksy, Wolfgang Tillmans, Eileen Quinlan, Daniel Gordon, Richard Mosse, Rinko Kawauichi, and artists like Olafur Eliasson. Or even fashion photographers like Nick Knight, Sølve Sundsbø, Bruno Aveillan and Erik Madigan Heck. So original great work is being created all over the world. It’s just that with digital technology and with the use of social media, a lot of mediocre work is also being seen and circulated.

Actually, in order to create authentic art, an artist needs to have a connect with history, society, and politics. In order to create, creativity should be a way of life for us; the way we live, think, perform and struggle shapes our creativity. In order to be creative, we need to strive for self-actualization. It is an undying urge to inquire, invent and act, and an inclination to identify valuable innovations. But most importantly, it is a process of planning, experiencing, interacting, and then allowing all of it to transform us in ways we never knew was possible. Now, all of this is very hard work and is a life-long pursuit of excellence. Only a few can walk this path, and that has always been the case. But even today, there are thousands who are still doing it. So, it becomes our responsibility as a viewer/critic/patron to acquire the knowledge and motivation to identify the creative or excellent from a sea of mediocre work.

Today we see a lot of photographers, using social media, following a common trend, fighting for likes and engagement. But many traditional photographers refrain from spending too much time on social media. Why do you think that is? Do you prefer being offline too? According to you, is social media an absolutely necessary tool for creatives around the world?

Social media is necessary for many creative individuals and organizations out there. And many of the ‘traditional’ photographers are using it very effectively. Like David Alan Harvey, Alex Webb, Alec Soth, Jacob Aue Sobol, Gueorgui Pinkhassov, Bruce Gilden, and so many more.

But I think for most of the ‘traditional’ photographers, the real world was what they wanted to explore, know more about, and interact with. They built their careers in the real world; in communities, in societies, in cultures, in journalism, in studios, in agencies, in galleries, in museums. But a lot of photographers recently have built their popularity on social media platforms like Instagram. Instagram is their only practice, career, and success. So it is quite natural for them to consider social media as unavoidable.

I have had discussions with so many photographers and artists who do not take social media seriously. But here, I can only speak for myself. I have realized that being on social media rarely helps my creativity or my ability to reach out to the right audience. Being on a platform like Instagram gives me this feeling that I have to somehow constantly feed a structure of information distribution that simply relies on the ‘likes’ of random strangers. It often leads to a point where I feel that to ‘post’ is more important than to actually produce work, when I know that eventually it would all be reduced to the number of my followers or the number of ‘likes’. I feel like someone is pulling me away from a considerate and systematic way of functioning that could produce something relevant and meaningful. I produce my work with a lot of effort, commitment and investment and the indifference or casualness with which it is received on social media is not very healthy for my creative process. I have been advised that ‘followers’ could be potential buyers, funders, or promoters, and that some of them could take my work to a wider audience. That could be true. But even then, this whole idea of looking at all these human beings as a ‘market’, to treat them as a ‘financial’ or ‘professional’ transaction, to constantly think what I could get from them, or how they could help my career, is quite demeaning to all these people. And then, to keep this hungry beast alive, constantly feeding it, with posts and stories and reposts and what not, is a lot of effort and time.

But I am aware of social media’s power and reach. So instead of dismissing it off, I use it at my own pace and the way I want to – posting or sharing just good work (a lot of it created by other photographers that I admire) without a hurry to garner followers or likes.

What other projects are you currently working on?

I have been researching about India’s history and its relationships with its minority communities, like the Dalits and Muslims. I am still reading and trying to identify what exactly I would want to say on this subject through photography.

Simultaneously, I am also working on a film along-with my friend and colleague, Chandan Gomes. We were to shoot the film in October this year. But like everyone else, we too are just waiting to see how the COVID situation might or might not affect our plans.

All Images by Bharat Choudhary.

Curated and Interviewed by Shrey Sethi.

One of the most important conversation which was needed in current scenario. Very truly and honestly put. Informative and kind of a reality check with outside world. Very well said that journey is indeed a destination.