All love letters are

Ridiculous.

They would not be love letters if

they were not

Ridiculous.

(Fernando Pessoa)

These lines might as well be the beginning of this article, just as they marked the starting point of Aditi Singh. A 40-minute short-film made by the French director Mickael Kummer in 2007, Aditi Singh is a marvel in its own existence. The film is based on the correspondence between the late 19th century author from Portugal, Fernando Pessoa, and the 19 year-old secretary that worked in the same office as him, Ophelia Queiroz. “When I showed my mentor Chantal Akerman the Pessoa poem, she was giddy and jumping like a child. She reacted just like I myself had when I first read it, and[making this film] was like rediscovering those texts”, recalls Kummer.

My first viewing of the film reminded me of Ritesh Batra’s The Lunchbox. The epistolary nature of the narrative, the presence of Mumbai streets and local trains within the film, and the escape that the two characters provide each other- scenes from The Lunchbox instantly appeared in my mind. Yet, this is not enough to compare the two films. They are merely using the same tune to perform a very different choreography. Aditi Singh is not meditative like Lunchbox, but is instead impulsive and reactionary.

Rajiv and Aditi, who work in the same office, are in a whirlwind of their own emotions and expectations from each other- like two teenagers testing the waters of attraction and love for the first time. Thoughts of each other constantly plague them; their desires overwhelm them. It makes one think of the kind of love we experience as school kids- one that is naive, boundless, and unafraid of thinking and promising a forever. It’s almost shocking to watch two adults performing such a dance on the screen.

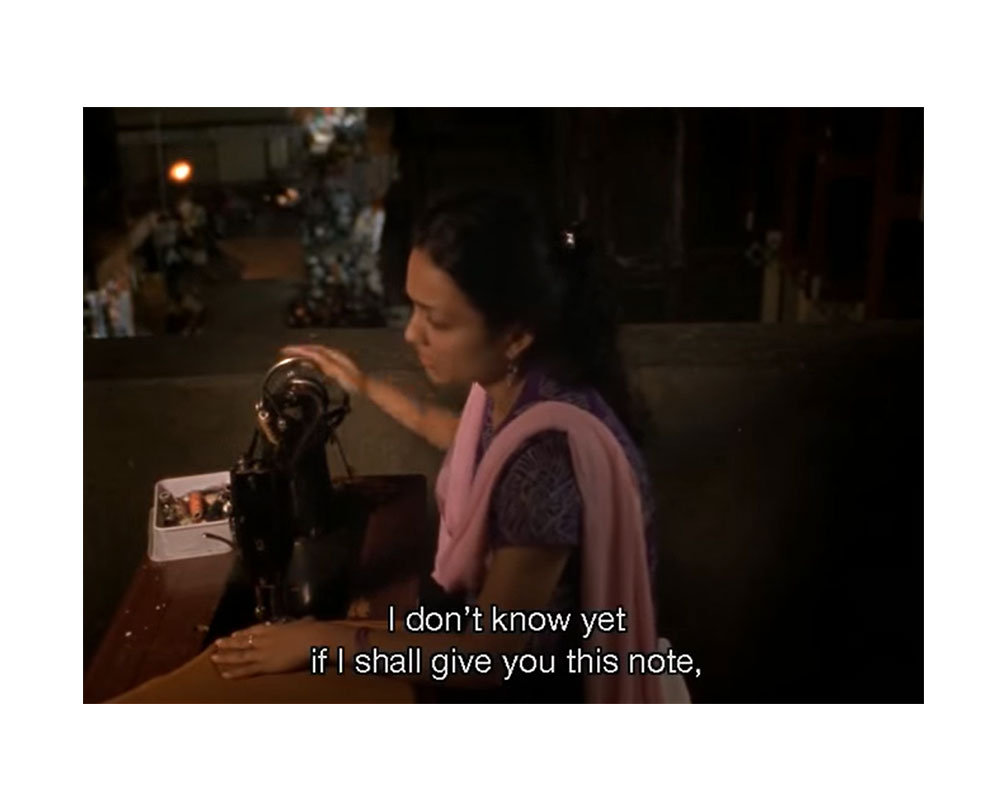

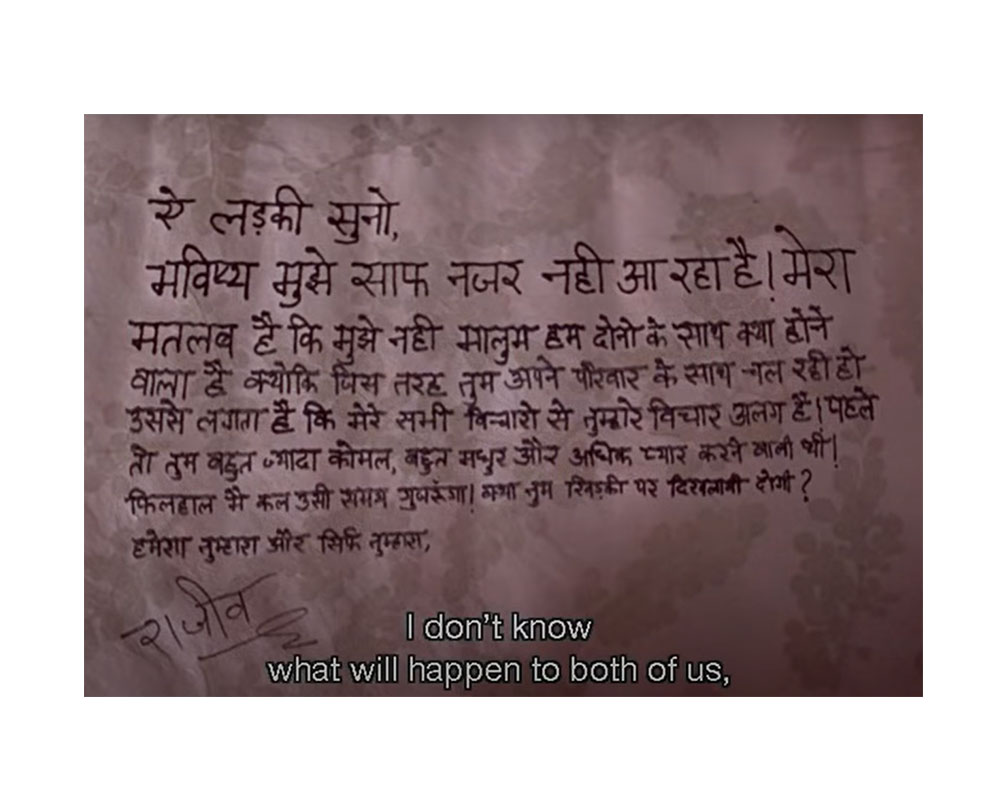

Yet, at the same time, it doesn’t feel superficial; perhaps because of the visual treatment of the film. The letters are sometimes only narrated, sometimes read out loud from a piece of paper. Because Kummer has used the original texts from Pessoa and Ophelia’s correspondence, Aditi’s letters had to be visualised to match to the way Ophelia had written hers. So her long, stream-of-consciousness writings are narrated by Aditi while she goes on about her day; time passing from day to night.

Her thoughts as she buys coconut water tell us what she wants to say to him, what plagues her, and are suddenly interjected by her haggling with the vendor on the price. Her pauses tell us which parts Ophelia must have written while going about her work, just as Aditi narrates sitting at her sewing machine, or hiding from an employee’s peeking eyes. The growing distance between the lovers is demonstrated by the large Mumbai crowd that separates them as they try to catch a glance of each other from afar.

Another such layer is added through the pauses in the way the shots are put together. In juxtaposition to the passion of the two characters, there are shots that take their time to settle into the characters’ emotions. The film still breathes when Aditi is troubled with her anger and frustration. In the conversation, Kummer also talked about applying ‘Distanciation’ in his planning of the film, which in general refers to a stepping back or distancing of the observer or reader from the object of scrutiny. The shots are blocked in a two dimensional way, and the focus is not on immersivity through visual beautification like, say, a Marvel film. The film allows you to watch detached from the characters’ tumultuous feelings. There are more wide frames with multiple characters than there are closeups. Shot by Pankaj Kumar (known for his work in films such as Ship Of Thesus, Tumbadd and Haider), Aditi Singh allows space for a love affair that belongs to its inspiration and not to the viewer. What Pessoa and Ophelia experienced is only for them, after all.

While much has been written about the original correspondence of the Portuguese writer and his lover by critics and academicians, what I too often came across during my research is cynicism, judgement and a complete lack of imagination. It was so, perhaps, because they were accusing Pessoa of ‘too much imagination’ through these letters; to the extent of calling the correspondence and the love affair “a heteronormative theatre” of his own creation.

But never mind; there’s still hope.

There is much about Aditi Singh that resides on the cusp of nostalgic romance, and modernity. The lovers’ correspondence and thoughts in the film is often interjected by scenes like the busy streets of Mumbai, the local trains, the watchful gaze of the people around them, and the rising prices of coconut water. The city and the society- both are a matter of concern for the idyllic world that the two lovers, Rajiv and Aditi, have created through their letters. Shot on 16mm film, Aditi Singh finds a way to time travel through the streets of 2007 Mumbai. In our conversation, Kummer mentioned that he was one of the last among his peers to still edit on film, as digital cameras had arrived and taken over by then. The office setting in which he chose to place the two characters, Rajiv being the boss and Aditi being a typewriter, is in the Mumbai University administrative office; it is a nostalgic space that still exists in 2007 when the world of IT structures with modern interior, computers and email, has taken over. With its metal almirahs, typewriters and paper, and one single space for all the employees to work- without the privacy of cubicles- this is a space that allows letters to be exchanged in secret.

As Garrison Keillor points out about this form of correspondence, “To be known by another person — to meet and talk freely on the page — to be close despite distance. To escape from anonymity and be our own sweet selves and express the music of our souls.”

And it is this quality of the film that makes it more fitting for a man such as Pessoa, and a story such as his and Ophelia’s; much more than the practical and surgical theories of academics. “I’ve always belonged to what isn’t where I am and to what I could never be,” he once wrote. And who are we to deny him that in our analysis of his own life? Kummer also talked about keeping Pessoa and his life in mind while choosing and extracting from the letters to build the narrative of the film. When I asked him about his decision to keep the one letter where Rajiv is just talking about how desperate he is for Aditi’s touch, and how ‘she is naughty for denying him that and deserves a whipping’, and ‘how he’s going to go dunk his head in a bucket of water now’, he laughingly mentions how Pessoa had humour in his life as well, so why not the film.

For a Bollywood inclined audience of 2007, Aditi Singh was a weird film. When I asked Kummer about it, he remembered the reactions he got from a screening in Bombay before it got a Cinefondation selection at the Cannes festival, 2007. “This one guy came out of the theatre […] and said “oh it was bad, they speak strange Hindi like in old Bollywood films!””, he told me, laughing. Today, I think we have grown as an audience. A professor of mine had once said about India,”’It is a demography so wide, the entire population can never exist on the same plane at the same time. People and communities are ever growing, they just have different starting points.” And this is exactly why a late 19th century love story can exist in 2007 India; as Kummer says when talking about his interest in the country and its cultural spaces, “What fascinates me most about India is that it allows travel through time.”

Aditi Singh, written and directed by Mickael Kummer, is currently available for streaming on MUBI as a part of their ongoing spotlight ‘Cannes Takeover’.

Stream 3 months of MUBI for free.

This story is a part of our ongoing partnership with MUBI India.

Written by Mansi Arora.